![Chagga men with war decoration, Tanzania, [s.d.]](https://tuebingen-moshi.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Chagga-Warriors-1-1065x399.jpg) Chagga Warriors

Chagga Warriors House building in Moshi

House building in Moshi![Machame, in Unga’s homestead before the beer, Tanzania, [s.d.]](https://tuebingen-moshi.de/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Meeting-in-Machame-e1707922541769-1095x410.jpg) Meeting in Machame

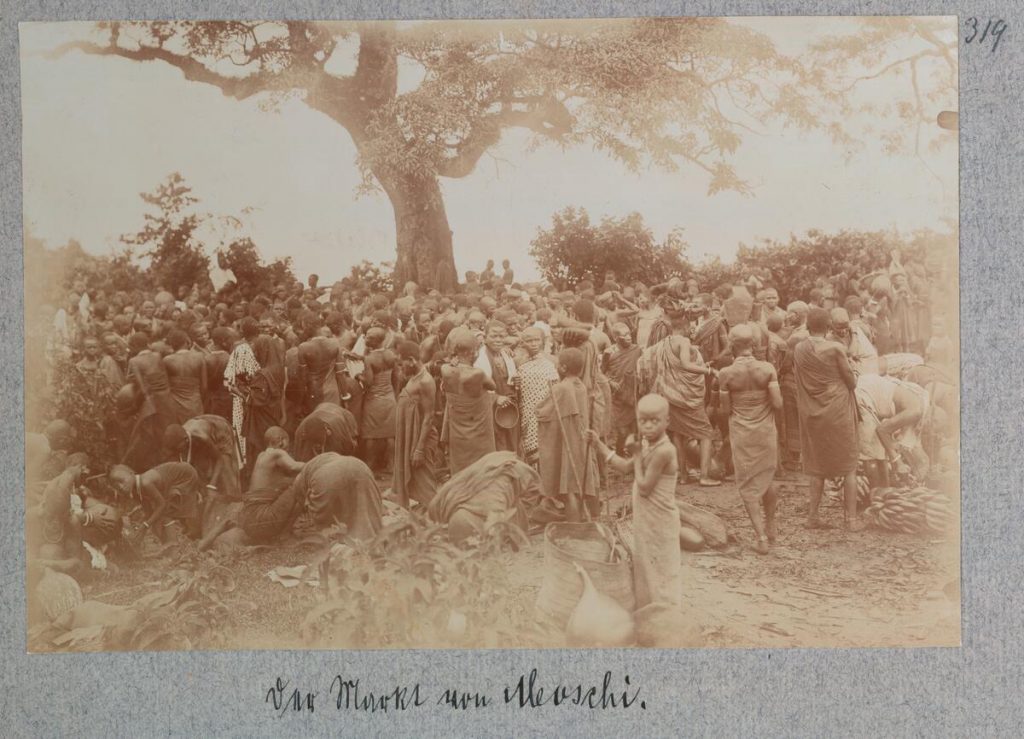

Meeting in Machame The Moshi market

The Moshi market

Das Recht der Dschagga

Das Recht der DschaggaThe law of the Wachagga

Das Recht der Dschagga (The Law of the Wachagga) not only presents the complex legal system of the Wachagga, but also provides detailed information about pre-colonial life and how society was structured: clan organization, age classes, family structure, the ruling system, the economy and everyday life. There are detailed reports on education systems and the transfer of knowledge, the position of women, but also, for example, house building. We can find also important examples of orally transmitted ‚writing‘ of history, a method later followed up by Kathleen M. Stahl in her groundbreaking work History of the Chagga People of the Kilimanjaro.

In contrast to the three volumes of Tribal Teachings, in which the pre-colonial knowledge is primarily documented (the complete material is presented on Kimoshi and then in a German translation) and Gutmann mostly holds back with assessments and evaluations, the aim of „Law of the Wachagga“ is different. It is indeed a treatise in the European sense of a scholarly work.

Gutmann not only documents, he establishes connections, links the present he describes with the pre-colonial past, evaluates and makes judgments. He also repeatedly criticizes the German colonial administration and makes suggestions, e.g. on how German justice can be better implemented. However, he does not question German rule or colonialism at any point. Nor does he consider Christianity and the original religion of the Wachagga to be of equal value. But this is all too understandable given his background as a missionary.

The source material is often only presented in a German translation, occasionally and more towards the end, parts are also handed down in the original Kimoshi and serve as a basis and to clarify his systematic presentation of the legal and social system. Nevertheless, it is fascinating and absolutely valuable how detailed and carefully he presents the knowledge gained at first hand and has preserved it in this way. It is a great piece of work.

In my opinion, however, an examination and precise reappraisal of the attitudes and opinions expressed by Gutmann would be urgently required in order to examine the extent to which there is an affinity with the „blood and soil“ ideology of the emerging National Socialism.

Hartmut Andres

menu

To find a topic or abstract more easily, you can use the key combination „CTRL + F“ (Win) or „CMD + F“ (Mac) to search for keywords or paragraphs within the pdf version of the book.

You can also copy text directly from the PDF file (OCR).

Due to the size of the file, we can not provide the book for preview here. Instead you will find it for download if you follow the button.

books

english

coming soon

swahili

coming soon

stories

ORIGINAL

Von Seite 332/326 ab, wird das folgende Ritual beschrieben, das einen wichtigen Teil der Jugendweihen und -lehren darstellte.

[…]

Die ausziehenden Burschen wurden feierlich um die alten Sippenhaine herumgeführt, um dann zu längerem Anschauungsunterrichte vor dem Haine Mungu im Bezirk Kidia gesammelt zu werden. Dieser Hain war ursprünglich der Aufenthaltsort für den Haingang. Er wurde dann aber verlassen, weil die Mbokomu-Leute als feindliche Nachbarn angeblich dort einen Hundsaffen und ein junges Mädchen vergraben hatten. Doch blieb in diesem Haine das Steinheiligtum der Mšiwu-Sippe zurück, ein großer schädelförmiger Flußstein, ihr sawo: Großvater, auch wuti genannt.

Dieser Stein ist nach der Sage durch Mrasi, den Ahnherrn der Mšiwu-Sippe nach Moschi gebracht worden. Der habe in seinem Sippenkreise die Jugendzucht und -lehre gepflegt in der Weise, wie sie nachher das ganze Land übernahm, als es durch den auffälligen Kinderreichtum der Sippe aufmerksam geworden war. Und da der Stein in den Lehren des Mrasi eine Rolle spielte, war es kein Wunder, daß er nach Mrasis Tode noch wichtiger wurde, weil er die Verehrung für den Begründer der Lehren auf sich zog. Er war unter zwei Palmen in die Erde eingegraben, umhüllt vom Fell der Opferziege des letzten Hainzuges. Beigegeben waren ihm Perlen von roter und schwarzer Farbe, durchlochte Scheibchen aus Straußeneierschalen und ein unterarmlanges Stück Elfenbein, der sogenannte Stier der Männer (tšau ja womi). Bepflanzt war die Stelle mit Dracänen und bestimmten Ritengräsern, die alle als Förderer der Zeugung und Pfleger neugeborenen Menschenlebens geschätzt wurden.

Am Tage vor dem Anmarsche opferte der Ritenalte mit seinem Anhange ein Schaf an der Stelle unter Gebeten an Mrasi um das Gedeihen des Hainzuges. Sie erinnern ihn daran, daß dies sein Stein sei, mit dem er die Jugend erzog. Er möge auch diesen Hainzug erwecken, wie er es im Anfang getan habe, daß die Knaben sich sänftigen und einander keinen Schaden tun, daß sie gedeihen und glänzen wie Elefantenfett, daß sie ausdauern wie die Dracäne an dieser Stelle, die nicht vertrocknet, daß sie sich aufrecken wie dieser Palmenbaum, der den sawo decke.

Wenn der Hainzug vor dem „Tore“ des Mungu-Gehölzes versammelt war, wurden ihm erst die alten heiligen Bäume gezeigt und zuletzt der Stein samt dem Elfenbeinstück unter Nennung ihrer Namen und der Betonung ihrer Herkunft und Ehrwürdigkeit. Die Burschen werden ermahnt, diese Kunde ihrerseits weiterzugeben an die zukünftige Jugend, so wie sie sie jetzt empfange. Die Handlung sollte sicher keine bloße Gedächtnisfeier sein, sondern der Anblick wohl Kraft übertragen. Bei der Darbietung des Elfenbeinstücks wurde z. B. gesagt: „Das ist der Stier der Männer. Er gibt euch Kindersegen und erhält die Kinder.“ Daran schloß sich der Rat, der Stätte treu zu bleiben, auch wenn jemand von ihnen auswandere also in Länder komme, die diesen Schatz nicht haben. Wenn dort der Ausgewanderte Kinder bekomme, möge er sich nachts etwas Erde von der Stelle holen, wo der Stein mit dem Stier vergraben liege und damit seinen Sohn salben. Dann lasse er ihn eine Nacht im Freien schlafen, um ihn darnach unter Aufsetzung des Bundesringes aufzunehmen als aus den Jugendweihen gekommen.

Form und Name deuten darauf hin, daß es sich bei dem Elfenbeinstück um einen Phallus handelt. Diese Darstellung wurde sehr wichtig genommen und war das erste Prüfungswerk, mit dem ein Bursche den Erwerb der Mannheit vor älteren Männern bewähren mußte. Aus fünf Fragen bestand es:

1. Der Torbaum, wer ist es?

Der Mšihio und Motsuo.

2. Hinter dem Tore, was ist da?

Der Hof.

3. Hinter dem Hofe deines Vaters, was ist da?

Der Milchbaum (eine Ban[i]ane)

4. Hinter dem Milchbaume, was ist da?

Der wuti (jener Stein).

5. Hinter dem wuti, was ist da?

Der Männerbund, ein Ort, der unsichtbar ist.

Die richtige Antwort lohnt der Spruch: „Kui mlume, kui mtana: Du bist ein Gelehrter, du bist ein Fertiger.“ Die letzte Antwort: m̄a womi kundo kulawono, deutet auf die Gleichsetzung mit der Geburt des Menschen, wo auch vom Gebilde im Mutterleibe gesagt wird, es sei wusuń, kundo kulawono.

ENGLISH

From page 332/326 onwards, the following ritual is described, which was an important part of the youth consecrations and teachings.

[…]

The departing lads were solemnly led around the old clan groves and then gathered in front of the Mungu grove in the Kidia district for a longer instruction session. This grove was originally the place for the „stay in the grove“. It was then abandoned, however, because the Mbokomu people, as hostile neighbors, had allegedly buried a dog ape [baboon] and a young girl there. However, the stone sanctuary of the Mšiwu clan remained in this grove, a large skull-shaped river stone, their sawo: grandfather, also called wuti.

According to legend, this stone was brought to Moshi by Mrasi, the ancestor of the Mšiwu clan. He cultivated the education and teaching of the youth in his clan in a way that was later adopted by the whole country when it became aware of the clan’s striking abundance of children. And since the stone played a role in Mrasi’s teachings, it was no wonder that it became even more important after Mrasi’s death, because the stone drew the veneration of the founder of the teachings to itself. It was buried in the ground under two palm trees, wrapped in the skin of the sacrificial goat from the last procession [into the grove]. It was accompanied by beads of red and black color, perforated slices of ostrich eggshells and a forearm-length piece of ivory, the so-called bull of men (tšau ja womi). The site was planted with dracaena and certain ritual grasses, all of which were valued as promoters of procreation and carers for newborn human life.

The day before the procession, the ritual elder and his followers sacrificed a sheep at the site, praying to Mrasi for the thriving of this procession into the grove. They reminded him that this was his stone with which he raised the youth. May he also revive this procession into the grove, as he did in the beginning, so that the boys may calm down and do no harm to each other, that they may flourish and shine like elephant fat, that they may endure like the dracaena in this place, which does not wither, that they may stretch up like this palm tree that covers the sawo.

When the procession [into the grove] had gathered in front of the „gate“ of the Mungu grove, they were first shown the old sacred trees and then the stone and the piece of ivory, mentioning their names and emphasizing their origin and venerability. The lads were admonished to pass this knowledge on to the future youth, just as they were receiving it now. The act was certainly not intended to be a mere commemoration, but the look at them was to transmit power. When the piece of ivory was presented, for example, it was said: „This is the bull of men. It gives you the blessing of having children and keeps them alive.“ This was followed by the advice to remain faithful to the site, even if one of them emigrated to countries that did not have this treasure. If the emigrant had children there, he should take some earth at night from the place where the stone with the bull were buried and anoint his son with it. Then let him sleep in the open air for a night after which he welcomes him, putting on the covenant ring, as having come from the youth consecrations.

The shape and name indicate that the ivory piece is a phallus. This presentation was taken very important and was the first examination with which a lad had to prove to older men that he had acquired manhood. It [the examination] consisted of five questions:

1. the gate tree, which one is it?

The Mšihio and Motsuo.

2. behind the gate, what is there?

The courtyard.

3. behind your father’s courtyard, what is there?

The milk tree (a banyan).

4. behind the milk tree, what is there?

The wuti (that stone).

5. behind the wuti, what is there?

The covenant of men, a place that is invisible.

The correct answer is rewarded by the statement: „Kui mlume, kui mtana: you are a savant, you are a finished one.“ The last answer: m̄a womi kundo kulawono, points to the equivalence with the birth of man, where it is also said of that which is formed in the womb that it is wusuń, kundo kulawono.

SWAHILI

Katika „Sheria ya Wachaga“ kuanzia ukurasa wa 332/326 na kuendelea, ibada ifuatayo inaelezwa, ambayo ilikuwa sehemu muhimu ya kufundisha na kuweka wakfu vijana.

[…]

Vijana waliokuwa wakiondoka waliongozwa kwa heshima kuzunguka misitu ya zamani ya ukoo kisha wakakusanywa mbele ya msitu wa Mungu wilayani Kidia kwa ajili ya mafunzo marefu zaidi. Hapo awali msitu huu ulikuwa mahali pa „kukaa msituni“. Baadaye uliachwa, hata hivyo, kwa sababu watu wa Mbokomu, kama majirani wenye uadui, walidaiwa kuzika nyani mbwa [nyani] na msichana mdogo huko. Hata hivyo, patakatifu pa jiwe la ukoo wa Mšiwu palibaki katika msitu huu, jiwe kubwa la mtoni lenye umbo la fuvu, sawo yao: babu, pia aliitwa wuti.

Kulingana na hadithi, jiwe hili lililetwa Moshi na Mrasi, babu wa ukoo wa Mšiwu. Alikuza elimu na mafundisho ya vijana katika ukoo wake kwa njia ambayo baadaye ilitumika na nchi nzima ilipofahamika uzuri mwingi wa watoto wa ukoo huo. Na kwa vile jiwe hilo lilikuwa na nafasi katika mafundisho ya Mrasi, haikua ajabu likawa muhimu zaidi baada ya kifo cha Mrasi, kwa sababu jiwe hilo lilivuta heshima ya mwanzilishi wa mafundisho hayo kwake. Lilizikwa ardhini chini ya mitende-nanasi miwili, likiwa limefungwa kwenye ngozi ya mbuzi wa dhabihu kutoka kwenye maandamano ya mwisho [kuingia msituni]. Ilisindikizwa na shanga za rangi nyekundu na nyeusi, vipande vilivyotoboka vya maganda ya mayai ya mbuni na kipande cha pembe ya ndovu kilichokuwa na urefu wa mkono, yule aliyeitwa fahali ya wanaume (tšau ja womi). Mahali hapo palipandwa dracaena na nyasi fulani za kiibada, vyote viki thaminiwa kama viwezeshi vya uzazi na walezi ya maisha machanga ya wanadamu.

Siku moja kabla ya maandamano, mzee wa ibada na wafuasi wake walitoa dhabihu ya kondoo mahali hapo, wakimuomba Mrasi ustawi wa msafara huu kuelekea ndani ya msitu. Walimkumbusha kwamba hili ni jiwe lake alilolelea vijana. Na afufue pia msafara huu kuelekea msituni, kama alivyofanya hapo mwanzo, ili wavulana watulie wasitendeane madhara, yakwamba wastawi na kung’aa kama mafuta ya tembo, waweze kustahimili kama dracaena katika eneo hili. mahali hapa, ambalo halinyauki, wapate kunyooka kama mtende-nanasi huu unaofunika sawo.

Msafara huo [kuelekea msituni] ulipokusanyika mbele ya „lango“ la msitu wa Mungu, walionyeshwa kwanza miti ya zamani iliyo wekwa wakfu na kisha jiwe na kipande cha pembe ya tembo, wakitaja majina yao na kusisitiza asili na heshima yao. Wavulana walihimizwa kurithisha ujuzi huu kwa vijana wa baadaye, kama vile walivyokuwa wakipokea sasa. Kitendo hicho kwa hakika hakikukusudiwa kuwa ukumbusho tu, bali mtazamo wao ulikuwa ni kuwapatia nguvu. Wakati kipande cha pembe ya ndovu kilipowasilishwa, kwa mfano, ilisemwa: „Hili ni dume la wanaume. Inakupa baraka ya kupata watoto na kuwaweka hai.“ Hii ilifuatiwa na shauri wa kubaki waaminifu wa mahali pale, hata ikiwa mmoja wao angehamia nchi ambayo hakukua na hazina hiyo. Ikiwa mhamaji huyo angepata watoto huko, angepaswa kuchukua udongo usiku kutoka mahali ambapo jiwe na fahali vilizikwa na kumpaka mtoto wake. Kisha amwache alale nje kwa usiku mmoja kisha amkaribishe, akimvisha pete ya agano, kama ametoka katika kuwekwa wakfu kwa vijana…

Sura na jina vinaonyesha kwamba kipande cha pembe ni phallus. Uwasilishaji huu ulichukuliwa kuwa muhimu sana na ulikuwa mtihani wa kwanza ambao mvulana alilazimika kuwathibitishia wanaume watu wazima kwamba amepata uanaume. [Mtihani huo] ulikuwa na maswali matano:

1. mti wa lango, ni upi?

Mšihio na Motsuo.

2. nyuma ya lango, kuna nini?

Ua.

3. nyuma ya ua wa baba yako, kuna nini?

Mti wa maziwa (banyan).

4. nyuma ya mti wa maziwa, kuna nini?

Wuti (hilo jiwe).

5. nyuma ya wuti kuna nini?

Agano la wanadamu, mahali pasipo onekana.

Jibu sahihi linatuzwa kwa kauli: „Kui mlume, kui mtana: wewe ni mtaalam, wewe umemaliza.“ Jibu la mwisho: ma womi kundo kulawono, inaonyesha sawa na kuzaliwa mwanaume, ambapo pia inasemwa juu ya kile kinacho undwa tumboni kuwa ni wusuń, kundo kulawono. „Sheria ya Wachaga“ 332/326 ff

ORIGINAL

Auch in den „Stammeslehren Band 1“, von S. 567/550 ab, wird dieses Ritual beschrieben:

[…]

Danach ordnet sich der Zug für den Aufmarsch in den Großhain Mūngu, der auf demselben Hügelrücken mit dem Haine Ngasiń liegt, zwanzig Minuten höher nach dem Bergwalde zu. In diesem Haine steht der wilde Ölbaum Mšihio, von dem die Zweige für das Ngasipeitschen genommen wurden, und stand der Milchbaum, eine Baniane, sein weibliches Gegenstück, und ruhte unter einem Palmbaume ein großer runder Stein zusammen mit der Spitze eines Elefantenzahnes, welche Stücke zusammengehörig sicherlich die Geschlechtskraft der Vorfahren versinnbildlichen sollten.

Stammeslehren 1 567/550

Die Burschen werden einzeln an jene Palme herangeführt, unter der, aus seiner Lederhülle befreit, ihnen ein großer runder Stein und danach die Spitze des Elefantenzahnes als der Blutbund der Männer gezeigt wird.

Von da kehren sie wieder unter den Ölbaum zurück und sitzen vor den Altherren nieder, die Beistände im Halbkreise hinter ihnen. Nachdem hinter dem letzten Burschen der Führer der Beistände vom Palmbaume herkommt, springt der Lehralte auf und singt den Burschen das Warnlied vom schiefen Blick und abweisenden Verhalten.

Stammeslehren 1 571/554

aus dem Lehrlied des Lehralten:

[…]

Und seitwärts vom Hofplatze den Milchbaum, den hast du gesehen.

Du hast alle Dinge gesehen, mein Jungbrüderlein.

Dein Altbruder hat dir auch deine schweigende Größe gezeigt.

Und er sprach zu dir: deine schweigende Größe im Geheimnisse, welch

[andere als nur diese, die du gesehen.

Ah, seitwärts der schweigenden Größe, da hat er dir auch den Blutbund

[der Männer gezeigt.

Und er sprach zu dir: dies ist der Blutbund der Männer, nicht länger

[darfst du geschmäht werden von Fraukindern.

Aber auch du unterlasse das Spielen mit den Fraukindern.

Wo sie die Ziegen hüten, da gehe du fort, mein Altersgenosse.

O ja heh hia aha.

Du Beistand des Kindes, höre zu.

Sage deinem Jungbruder vom abweisenden Verhalten.

Oh ja, heh hia aha.“*

*Iwuti heißt der große runde Stein und das bedeutet „die schweigende Größe“ Dazu gehört noch die Spitze eines Elfenbeinzahnes. Der wird im Liede Blutbund der Männer genannt. Gewöhnlich heißt er tšau ja womi: Stier der Männer.

Stammeslehren 1 572-3/555-6

ENGLISH

This ritual is also described in the „Tribal Teachings Volume 1“, from p. 567/550 onwards:

[…]

Afterwards, the procession marched to the grand grove of Mūngu, which lies on the same ridge as the Ngasiń grove, twenty minutes higher up towards the mountain forest. In this grove stands the wild olive tree Mšihio, from which the branches for the Ngasi whips were taken, and stood the milk tree, a banyan, its female counterpart, and under a palm tree rested a large round stone together with the tip of an elephant’s tusk, which pieces together were certainly intended to symbolize the sexual power of the ancestors.

Tribal teachings Vol. 1 567/550

The lads are led one by one to the palm tree under which, freed from its leather covering, they are shown a large round stone and then the tip of the elephant’s tusk as the blood covenant of men.

From there they return under the olive tree and sit down in front of the old men, the advisors in a semicircle behind them. After the leader of the advisors comes from the palm tree behind the last lad, the teaching elder jumps up and sings the warning song to the lads about the wry look and dismissive behavior.

Tribal teachings Vol. 1 571/554

from the teaching song of the teaching elder:

[…]

And beside the courtyard square, the milk tree, you have seen it.

You have seen all things, my little younger brother.

Your elder brother also showed you your silent greatness.And he said to you: your silent greatness in the secret, what other than just this one that you have seen.

Ah, beside the silent greatness, he also showed you the blood covenant of men.

And he said to you: this is the blood covenant of men, you must no longer be reviled by the woman-children.

But you too must refrain from playing with the woman-children.

Where they herd the goats, there you go away, my age-mate.

O ja heh hia aha.

You, child’s advisor, listen.

Tell your younger brother about the dismissive behavior.

Oh ja, heh hia aha.“*

*Iwuti is the name of the large round stone and means „the silent greatness“. In addition, there is the tip of an ivory tusk. It is called the blood covenant of men in the song. It is usually called tšau ja womi: bull of the men.

Tribal teachings Vol. 1 572-3/555-6

SWAHILI

Tambiko hili limefafanuliwa pia katika „Mafundisho ya Kikabila Juzuu ya 1“, kutoka uk. 567/550 kuendelea:

[…]

Baadaye, msafara huo uliandamana hadi kwenye msitu mkubwa wa Mūngu, ambao uko kwenye mwinuko uleule wa msitu wa Ngasiń, dakika ishirini kwenda juu kuelekea msitu wa mlima. Katika msitu huu umesimama mzeituni mwitu Mšihio, ambapo matawi ya mijeledi ya Ngasi yalichukuliwa, na kusimama mti wa maziwa, banyan, mwanamke mwenzake, na chini ya mtende-nanasi kulikuwa na jiwe kubwa la mviringo pamoja na ncha ya pembe ya tembo, ambayo vikiwa pamoja vilikusudiwa kuashiria nguvu ya kijinsia ya mababu.

Mafundisho ya kikabila Vol. 1 567/550

Vijana hao wanaongozwa mmoja baada ya mwingine hadi kwenye mtende-nanasi ambao chini yake, ukiwa umeachwa tupu toka kifuniko chake cha ngozi, wana onyeshwa jiwe kubwa la mviringo na kisha ncha ya pembe ya tembo kama agano la damu la wanaume.

Kutoka huko wanarudi chini ya mzeituni na kukaa chini mbele ya wazee, washauri katika nusu duara nyuma yao. Baada ya kiongozi wa washauri kutoka kwenye mtende nanasi nyuma ya kijana wa mwisho, mzee wa kufundisha anaruka na kuimba wimbo wa onyo kwa vijana kuhusu kuangalia kwa kushuku na tabia ya kutojali.

Mafundisho ya kikabila Vol. 1 571/554

Kutoka kwa wimbo wa mafundisho wa mzee wa kufundisha.

[…]

Na kando ya mraba wa ua, mti wa maziwa, umeuona.

Umeona mambo yote, mdogo wangu mdogo wa kiume.

Kaka yako pia amekuonyesha wewe ukuu wako wa kimyakimya.

Naye akakuambia: ukuu wako wa kimyakimya sirini, ni nini zaidi ya hili tu ambalo umeona. Ah, kando ya ukuu wa kimyakimya, alikuonyesha pia agano la damu la wanaume. Naye akakuambia: Hili ni agano la damu la wanaume, msitukanwe tena na watoto wa kike.

Lakini wewe pia lazima ujiepushe na kucheza na watoto wa kike. Huko wanachunga mbuzi, huko unakwenda mbali, mrika mwenzangu. O ja heh hia aha. Wewe, mshauri wa mtoto, sikiliza. Mwambie mdogo wako wa kiume kuhusu tabia ya kutojali. Oh ja, heh hia aha.“*

*Iwuti ni jina la jiwe kubwa la mviringo na linamaanisha „ukuu wa kimyakimya“. Kwa kuongeza, kuna ncha ya pembe ya ndovu. Inaitwa agano la damu la wanaume katika wimbo. Kwa kawaida huitwa tšau ja womi: fahali wa wanaume.

Mafundisho ya kikabila Vol. 1 572-3/555-6

ORIGINAL

Über den Verbleib dieses Steins (Iwuti) gibt Gutmann in der folgenden Erzählung Auskunft:

Der Heidenstein1

Unter dem 4. Juni 1896 findet sich in das Stationsbuch eingetragen, was folgt: „Zum Zwecke des Hausbaus mußten wir einen Teil des auf dem Stationsplatze üppig grünenden Gebüsches umhauen. Die Besorgnis, wir würden sämtliche Büsche abhauen, mag der Anlaß gewesen sein, daß heute mittag einige Greise kamen und im Verein mit anderen meist älteren Leuten aus den Eingeborenen baten, ‚ein Ding ihrer Sitte‘ von unserem Grundstück wegnehmen zu dürfen. Sie erklärten auf Befragen nicht deutlich, was das für ein Ding sei. Ihre Bitte wird ihnen gewährt. Es stellte sich heraus, daß ein in der Nähe einer Phönixpalme in die Erde gegrabener großer runder Stein, der bei der Beschneidung des männlichen Geschlechts eine Rolle spielt – die Neubeschnittenen versammelten sich einst dort, während die Alten insgeheim ihre Zeremonien dabei verichteten – gemeint war. Als Faßmann hinzukam, fand er die Greise eben dabei, ein herzugebrachtes Schaf mehrmals im Kreise über der wichtigen Stelle herumzudrehen. Einer legte sodann die Hand auf den Kopf des knienden Tieres und murmelte einige Faßmann nicht verständliche Worte, ebenso tat ein Zweiter. Das Schaf wurde auf den Rücken gelegt, einer schnitt ein Stückchen Ohr ab, um dann in die Brust zu stechen, wobei dem Tier das Maul zugehalten wurde. Von dem wenigen aus der Wunde dringenden Blute tat man etwas auf die heilige Stelle. Zur Verwunderung Faßmanns war das Schaf, ohne geschrien zu haben, alsbald tot. Der Stich war offenbar ins Herz gegangen, außerdem Erstickung erfolgt. Die Alten hoben den Stein aus, in die Höhlung aber kam ein wenig von dem Bauchinhalt des Tieres, das nur leicht aufgeschnitten worden war, außerdem ein Stück Klaue und die Zungenspitze. Man hüllt den Stein in ein Stück Zeug, nachdem ein Fell darüber gebreitet. Eine kleine Differenz entsteht, welcher Teilnehmer am Werk den gewichtigen Stein tragen soll. Endlich nimmt ihn einer entschlossen auf sich, oder vielmehr läßt ihn sich auf den Kopf legen – Auch das Schaf wir zusammengebunden und weggetragen. Der Stein wurde nach einem anderen Platze geschleppt und wohl dieser andere Ort für ihn geweiht. Faßmann schickte einen Jungen nach, zuzusehen, wo der Stein hingetragen würde, aber man ließ den Burschen nicht hinzukommen, sondern hielt ihn fern, wie man bei Aushebung des Steins auf unserem Grundstücke die jungen Leute aus der Nähe gewiesen hatte.“

Dieser Stein war das letzte Stück, das die Altherren zu retten versuchten von dem Geheimnis der Männer und ihres Blutbundes, das von dem Großhaine des Landes umschlossen gewesen war. Zu diesem Basaltstein hat noch die Spitze eines Elefantenzahns gehört. Der war aber schon damals verlorengegangen, als die Soldaten der Ostafrikanischen Gesellschaft die Station bevölkerten. Ihres Ruhmes beraubt, stand nun die Phönixpalme allein. Den „Beistand der Frauen“ hatte man sie genannt und sie damit zu einem Gegenstück des Trutzbaums gemacht, der auch noch den Ehrennamen „Ehebeistand der Männer“ trug. Es hat nicht mehr lange gedauert, dann ist auch diese Palme gefallen und für eins der vielen Nebengebäude mit verwendet worden. Doch immer treiben Schößlinge an der Stelle, wo sie einst Wurzel geschlagen hatte. Aber rund um diese Schößlinge her steht die neue Pflanzung als geschlossener Wald. Der Stein überdauerte alle Schicksale. Er gehört der Sippe des Mschiu oder Matscha. Seine Form gleicht einem Schädel. Wahrscheinlich ist es ein Ahnenstein, den der erste Einwanderer mitbrachte, oder er ist als Stellvertreter für die Ahnen in der alten Heimat oder für einen im Krieg Gefallenen einstmals eingesetzt worden. Darauf deutet auch die Art seiner Verwendung in den Stammeslehren. Er wurde da den Novizen nur gezeigt, wie man in den Sippenhainen sonst die Schädel der Ahnen darzustellen pflegte. Diese Darstellung war eine Aussetzung auch seiner Kräfte und die Verpflichtung auf sein Geheimnis, bei dem man nur als Miteingeweihter schwören durfte.

Als die Altherren den Stein ausgegraben hatten, brachten sie ihn nicht weit, sondern setzten ihn auf dem Platze nieder, wo sie ihren Neujahrstanz zu springen pflegten. Aber um die Ruhe des alten Heidensteines war es dennoch geschehen. Die Altherren konnten ihn nicht mehr vor dem Übermute der neuen Jugend hüten. Die wußte nur noch so viel von ihm, daß er der Verkörperer der Mannheit ihrer Väter gewesen war. Sie aber verwandelten ihn nun zu einem Erprober der Manneskraft. Als reif zur Ehe sollte nur gelten, wer imstande war, den schweren Stein frei vom Boden aufzunehmen und, ohne ihn von der Brust abzustemmen, sich auf den Kopf zu legen und zu tragen. Das wurde ein ungeschriebenes Gestz der damaligen Altersklasse. So mancher schlich sich heimlich zum Stein und übte an ihm seine Kräfte, um vor den Kameraden ohne Tadel zu bestehen. Dadurch verlor der Stein seine Schutzhüllen und die ihm gezollte Ehrerbietung. Nur seine Schwere verhinderte es, daß er nicht allzu weit verschleppt wurde und schließlich ganz verlorenging. Aber die Gefahr dazu bestand.

Das bedachten auch zwei Knaben, die im Dienst des Missionars täglich in der Nähe des Steins beschäftigt waren und das Treiben der älteren Genossen mit ansehen mußten. Sie sagten zueinander: Wenn das so weiter geht, ist eines Tages der Stein verloren. Woran sollen wir dann unseren Ruhm gewinnen und unsere Mannheit erproben, wenn wir herangewachsen sind? Sie kamen rasch zu einem Einverständnis, und trugen den Stein gemeinsam zurück in die Nähre des Ortes, wo er zuerst gewesen war, und versteckten ihn bei ihrer Schlafhütte. Verborgen blieb er freilich nicht lange. Hatten sie ihn doch für ihre Altersklasse gerettet, und die übte nun heranwachsend ihre Kräfte an ihm. Fast zwei Jahrzehnte lang lag er so offen auf einem Platze nahe der Kirche, bis es der neuen Jugend einfiel, ihn zu ihrem Spielplatz zu tragen und sich dort an ihm zu üben. Das gefiel aber jenem Manne nicht, der ihn einst als Knabe mit einem Kameraden in Sicherheit gebracht hatte.

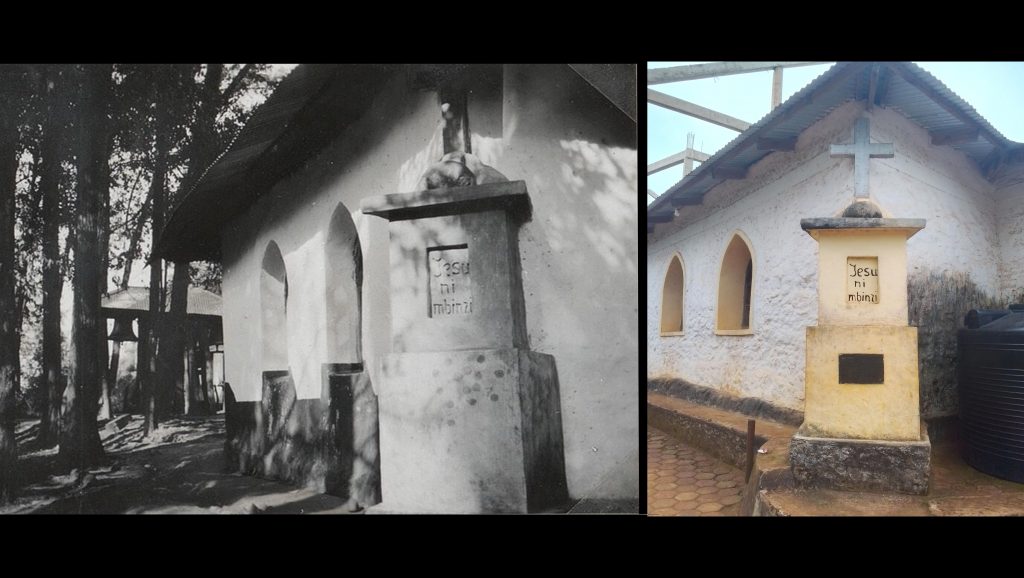

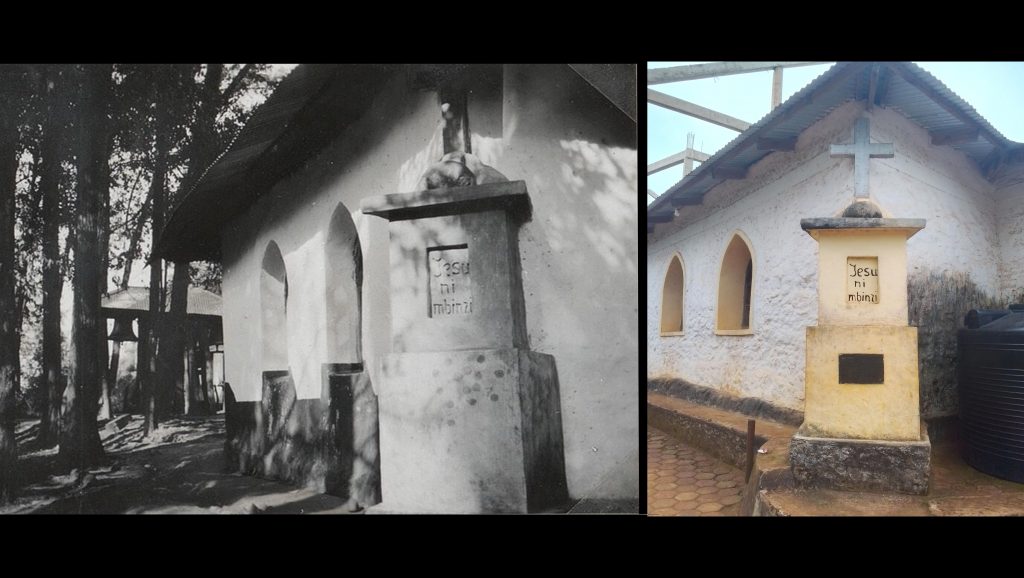

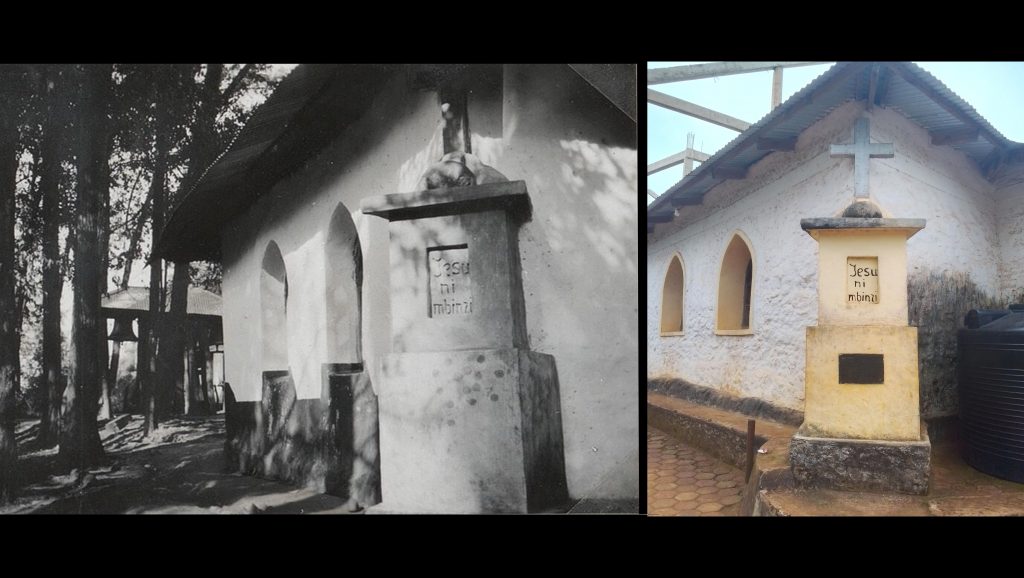

Eines Tages war der Stein wieder verschwunden. Als ich seinem Verbleib nachforschte, meldete sich dieser Mann und vertraute mir an, daß der Stein auf seinem Hofe wohl geborgen sei. Aber auf den Spielanger dürfe er nicht zurück. Dort würde es sonst nicht lange dauern, bis er ganz verlorengegangen sei. Das sah ich ein und beließ ihm vorerst den Stein. Aber mir lag daran, ihn für die Nachwelt und die Wissenschaft zu erhalten. Die Gelegenheit dazu bot sich mir, als es notwendig wurde und eine großherzige Spende es ermöglichte, das alte Gotteshaus auszubessern. Die nordöstliche Ecke des Chors drohte einzustürzen. Es stellte sich heraus, daß die damaligen Werkleute einfach Stein auf Stein gelegt hatten, ohne sie nach irgendeiner Seite zu binden. Bei der Bauart des Gebäudes schien es nicht geraten, einfach diese Ecke niederzulegen und neu aufzuführen, sondern sie bedurfte, wollte man dem ganzen Gebäude größere Sicherung geben, einer besonderen Stütze durch eine Futtermauer.

Aus dieser Futtermauer entwickelte sich aber ein Mahn- und Siegesmal. In den wuchtigen Zementsockel wurde eine Tafel eingelassen mit der Inschrift: Jesu ni Mbinzi – Jesus ist Sieger. Darüber kam als Platte ein alter Dschaggamahlstein, auf dem man das Korn zerrieb. Diese Platte bekrönt ein hohes Zementkreuz, das der Mauer noch bis zum Dachrand Halt gibt. Der Fuß dieses Kreuzes ruht auf dem Heidensteine, der hier endlich seine Ruhestätte gefunden hat. Hier führt er der Gemeinde Gottes vor Augen, daß sie einst zu den toten Steinen geführt worden sind, nun aber dienen dem lebendigen Gott. Als der Schädelstein aber vertritt er die ganze menschliche Natur, wie sie von Adam her dem Tode geweiht ist. Über ihn ragt das Kreuz auf und bekennt den, der dem Tode die Macht genommen und ein unvergängliches Wesen ans Licht gebracht hat mit der Auferstehung. Jesus ist Sieger und hat auch diesen Heidenstein entsiegelt, daß die Sehnsucht nach einem starken, zuchtvollen und fruchtbringenden Leben, die sich einst an ihn hing, nun über ihm die wahre Erfüllung finde und in den Dienst der echten Kindschaft weise.

1 Der Begriff „Heidenstein“ ist von Bruno Gutmann gewählt. Er zeigt seine Sicht als Missionar. Seine Haltung wird auch im letzten Abschnitt des Textes deutlich, wo er den Stein so einbauen lässt, dass der Triumph des christlichen Glaubens über die ursprüngliche Religion der Wachagga sichtbar wird. Er deutet die alte Bedeutung des Steins in einem christlichen Sinn um und zeigt durch die Anordnung von Stein und Kreuz den Sieg des Christentums.

aus:

„Unter dem Trutzbaum“ S. 29 ff

ENGLISH

Gutmann provides information about the further history and whereabouts of this stone (Iwuti) in the following story:

The heathen stone1

On 4 June 1896, the following is entered in the Ward Book [of the Lutheran mission station]: „For the purpose of building a house we had to cut down part of the lush green bushes on the ward square. The concern [fear] that we would cut down all the bushes may have been the reason why some old men came at noon today and, together with other mostly elderly people from the indigenous community, asked to be allowed to take away ‚a thing of their custom‘ from our property. When questioned, they did not clearly explain what this thing was. Their request was granted. It turned out that a large round stone dug into the ground near a phoenix palm tree, which plays a role in the circumcision of the male [sex] – the newly circumcised once gathered there while the old people secretly conducted their ceremonies there – was meant. When Faßmann arrived, he found the old men turning a sheep that had been brought in several times around over the important spot. One of them then put his hand on the head of the kneeling animal and murmured a few words that Faßmann could not understand. The sheep was put on its back, one of them cut off a piece of the ear and then stabbed into the chest, holding the animal’s mouth shut. Some of the little blood that came out of the wound was put on the sacred spot. To Faßmann’s astonishment, the sheep died immediately without having cried out. The stab had obviously gone into the heart and it had suffocated. The old men dug out the stone, but into the cavity came a little of the animal’s stomach contents, which had only been slightly cut open, as well as a piece of claw and the tip of the tongue. The stone was wrapped in a piece of cloth after a fur had been spread over it. A small difference [of opinion] arises as to which participant in the work should carry the weighty stone. Finally, one of them resolutely takes it on himself, or rather has it placed on his head. The sheep was also tied together and carried away. The stone was dragged to another place and this other place was consecrated for it. Faßmann sent a boy to see where the stone would be carried, but the boy was not allowed to come, but was kept away, just as the young people had been kept away when the stone was dug out on our property.“

This stone was the last piece that the old men tried to save from the secret of the men and their blood covenant, which had been enclosed by the great [sacred] grove of the land [that originally was located on this site]. The tip of an elephant’s tusk belonged to this basalt stone. But it had already been lost when the soldiers of the East African Society populated the station. Deprived of its glory, the phoenix palm now stood alone. It had been called the „Women’s Succour“, making it a counterpart of the „Trutzbaum“2, which also bore the honorary name „Men’s Marriage Succour“. It was not long before this palm tree also fell and was used for one of the many outbuildings. But there are always shoots sprouting from the place where it once took root. But around these shoots, the new plantation stands as a closed forest. The stone outlasted all fates. It belongs to the clan of Mshiu or Matsha. Its shape resembles a skull. It is probably an ancestor stone brought by the first immigrant, or it was once used as a representative for the ancestors in the old homeland or for someone killed in war. This is also indicated by the way it was used in tribal teachings. He was only shown to the novices, as the skulls of the ancestors were usually displayed in the clan groves. This presentation was also an exposure of his powers and the obligation to his secret, by which one was only allowed to swear as a fellow initiate.3

When the old men had dug out the stone, they did not take it far, but set it down in the place where they used to jump their New Year’s dance. But the peace of the old heathen stone was gone. The old men could no longer protect it from the cockiness of the new youth. The latter knew only so much about it, that it had been the embodiment of the manhood of their fathers. But they now transformed it into a trier of manhood. Only those who were able to pick up the heavy stone freely from the ground and, without lifting it from their chest, to place it on their head and carry it, were to be considered mature for marriage. This became an unwritten law of the age class of the time. Many a person would secretly sneak up to the stone and practise his strength on it in order to pass without blame in front of his comrades. In this way, the stone lost its protective covers and the reverence paid to it. Only its weight prevented it from being carried too far and finally being lost completely. But the danger existed.

Two boys, who were in the missionary’s service every day near the stone and had to watch the activities of the older comrades, also thought about this. They said to each other: „If this goes on, one day the stone will be lost. Then what shall we use to gain our glory and test our manhood when we have grown up? “ They quickly came to an agreement, and together they carried the stone back to the vicinity of the place where it had first been, and hid it near their sleeping hut. Of course, it did not remain hidden for long. After all, they had saved it for their age class, which was now practising its strength on it as it grew up. For almost two decades it lay open in a square near the church, until the new youth remembered to carry it to their playground and practise on it there. But this did not please the man who had once brought it to safety as a boy with a comrade.

One day the stone had disappeared again. When I investigated its whereabouts, this man came forward and informed me that the stone had been saved on his homestead. But it was not allowed to return to the playground. Otherwise it would not be long before it was completely lost. I understood this and left him the stone for the time being. But it was important to me to preserve it for posterity and science. The opportunity to do so presented itself to me when it became necessary and a generous donation made it possible to repair the old church. The northeast corner of the choir was in danger of collapse. It turned out that the workmen of that time had simply laid stone on stone without connecting them to any side. Given the nature of the building, it did not seem advisable to simply put down this corner and rebuild it, but in order to give the whole building greater security, it needed special support in the form of a retaining wall.

However, this retaining wall developed into a memorial and victory monument. A plate with the inscription: „Jesu ni Mbinzi – Jesus is victor“ was set into the massive cement base. On top of it was placed an old Chagga grinding stone, a slab on which the grain was grinded. This slab is crowned with a high cement cross, which supports the wall up to the edge of the roof. The foot of this cross rests on the heathen stone, which has finally found its resting place here. Here it shows to the congregation [community] of God that they were once led to the dead stones, but now serve the living God. As the skull stone, however, he represents the whole of human nature as it has been dedicated to death since Adam. The cross towers above him and confesses the one who took the power of death and brought an everlasting being to light with the resurrection. Jesus is the victor and has also unsealed this heathen stone, so that the longing for a strong, chaste and fruitful life, which once clung to it, may now find true fulfillment above it and be directed to the service of true filiation.

1 The term „Heathen Stone“ was chosen by Bruno Gutmann. It shows his view as a missionary. His attitude also becomes clear in the last section of the text, where he has the stone installed in such a way that the triumph of the Christian faith over the original religion of the Wachagga becomes visible. He reinterprets the ancient meaning of the stone in a Christian sense and shows the victory of Christianity through the arrangement of stone and cross. The term was left here as an expression of Gutmann’s attitude. In today’s usage, however, I no longer consider this term appropriate. Perhaps a term like “ Ancestors‘ Stone“ or „Ritual Stone“ would be better. In any case, this should be discussed in Old Moshi with the involvement of the owners, the Mšiwu clan.

2 „Trutzbaum“ – „defiance tree“: a tree that braved, that resists. Gutmann has named an old sacred tree in this way, a remnant of the sacred grove that still stood in his lifetime.

3 see also „The Tribal Teachings“ Volume 1 from page 550 onwards (see above)

from:

„Unter dem Trutzbaum“ p. 29 ff

Translation into English by Hartmut Andres, [additions in square brackets].

SWAHILI

Gutmann provides information about the further history and whereabouts of this stone (Iwuti) in the following story:

Jiwe la Wapagani1

Tarehe 4 Juni 1896, yafuatayo yaliandikwa katika Kitabu cha Kata (cha kituo cha misheni cha Kilutheri): “Ili tuweze kujenga nyumba, tulilazimika kufyeka baadhi ya vichaka vya kijani vilivyositawi kwenye eneo la kata. Wasiwasi kwamba tungefyeka vichaka vyote huenda ndio sababu ya wazee kufika mchana wa leo wakiambatana na watu kadhaa, wengi wao wakiwa ni wazawa asilia, na kuomba waruhusiwe kuchukua kitu chao cha kimila kutoka kwenye eneo letu. Walipoulizwa ni kitu gani, hawakueleza wazi. Ombi lao lilikubaliwa. Baadae ilibainika kuwa kilichokusudiwa ni jiwe kubwa la umbo la tufe lililochimbiwa ardhini karibu na mtende-nanasi, ambao ulitumika kipindi cha tohara kwa vijana wa kiume (watahiriwa walikusanyika hapo wakati wazee wakifanya kwa siri sherehe zao). Fassmann alipofika, aliwakuta wazee wakimgeuza kondoo ambaye alikuwa ameletwa mara kadhaa kwenye sehemu hiyo muhimu. Kisha mmoja wao akaweka mkono wake juu ya kichwa cha mnyama huyo aliyepiga magoti na kunong’ona maneno machache ambayo Faßmann hakuweza kuyaelewa. Kondoo alilazwa chali na mzee mmoja akamkata kipande cha sikio na kisha kumchoma kisu kifuani huku akiuziba mdomo wa mnyama huyo. Damu kidogo kutoka kwenye jeraha iliwekwa pale mahali patakatifu. Faßmann alishangaa kuona kondoo akifa mara moja bila kutoa mlio. Kisu kilikuwa kimemchoma moyoni na kumuua papohapo.

Wazee walichimbua jiwe, lakini ndani ya kishimo ulikuwepo utumbo wa mnyama, ambaye alikuwa amepasuliwa kidogo tu, na kiipande cha kwato na ncha ya ulimi. Jiwe hilo lilifungwa kwa kitambaa baada ya kuzungushiwa manyoya. Mabishano kidogo yalitokea kuhusu ni nani anapaswa kubeba jiwe hilo zito. Hatimaye, mtu mmoja alilichukua kwa uthabiti na kulibeba juu ya kichwa chake. Kondoo pia alifungwa na kuchukuliwa. Jiwe lilipelekwa sehemu nyingine iliyotiwa wakfu kwa ajili yake. Faßmann alimtuma mvulana mmoja kuona mahali ambapo jiwe lilipelekwa, lakini mvulana huyo hakuruhusiwa kufuatana nao, kama ambavyo vijana wengine walivyozuiliwa wakati jiwe lilipochimbuliwa kwenye eneo letu.“

Jiwe hili lilikuwa kitu cha mwisho ambacho wazee walijaribu kuokoa kutokana na siri ya watu na agano lao la damu, ambalo lilikuwa limezungukwa na msitu mkuu mtakatifu wa nchi yao ambao hapo awali ulikuwa kwenye eneo hili. Ncha ya jino la ndovu ilikuwa sehemu ya jiwe hili. Lakini ilikuwa tayari imepotea wakati askari wa Chama cha Afrika Mashariki walipojazana kwenye kituo. Mtende-nanasi sasa ulisimama peke yake, baada ya kunyimwa utukufu wake. Ulikuwa umeitwa „muawana wa wanawake“, na kuufanya kuwa sehemu ya „Trutzbaum“, ambao pia ulikuwa na jina la heshima „muawana wa ndoa za wanaume“. Haikupita muda mtende huu pia ukaanguka na ukatumiwa kujenga mojawapo ya mabanda.

Mara nyingi machipukizi yalichomoza kutoka mahali ilipoota mizizi ya mti. Lakini kuzunguka mashina haya, kuna shamba jipya lililosimama kama msitu uliojifunga. Lile jiwe lilishinda majaribu yote. Ni la ukoo wa Mshiu au Macha. Umbo lake linafanana na fuvu. Labda ni jiwe la mababu wa kale lililoletwa na mhamiaji wa kwanza, au lilitumika kama mwakilishi wa mababu katika nchi ya zamani au kwa mtu aliyeuawa vitani. Hii pia inadhihirishwa na jinsi lilivyotumiwa katika mafundisho ya kimila. Lilionyeshwa tu kwa wanagenzi, kwani kwa kawaida mafuvu ya mababu yalionyeshwa kwenye vijisitu vya ukoo. Uwakilishi huu pia ulifanywa kuonesha mamlaka yake na wajibu wa siri yake, ambayo mtu aliruhusiwa tu kuapa kama mwari mwenza.

Wazee walipolichimbua lile jiwe, hawakulipeleka mbali bali waliliweka sehemu ambapo walikuwa wakicheza ngoma yao ya mwaka mpya. Lakini amani ya jiwe la kale la kipagani ilitoweka. Wazee hawakuweza tena kulilinda dhidi ya ujanja wa vijana wa kizazi kipya. Vijana hawa walilitambua tu kama kielelezo cha uanaume wa baba zao. Sasa waliligeuza kuwa kipimo cha uanaume. Wale tu walioweza kulibeba jiwe lile zito kutoka chini na kuliweka juu ya vichwa vyao bila kuliweka kifuani, ndio walichukuliwa kuwa watu wazima wa kuweza kuoa. Hii ikawa sheria isiyoandikwa ya rika la wakati huo. Vijana wengi walienda kwenye jiwe kisirisiri na kujipima nguvu ili kushinda bila lawama kutoka kwa wenzao. Kwa njia hii, jiwe lilipoteza thamani yake ya ulinzi na heshima lililopewa mwanzo. Uzito wake pekee ndio uliozuia kubebwa na hatimaye kupotezwa kabisa. Lakini hatari ilikuwepo.

Wavulana wawili waliokuwa wakitumikia mishonari kila siku karibu na jiwe walijikuta wakishuhudia shughuli za ndugu wakubwa, nao walifikiria kuhusu hili. Wakasemezana wao kwa wao: „Hii tabia ikiendelea, siku moja jiwe litapotea. Sasa tutatumia nini kupata utukufu wetu na kupima uanaume wetu tukiwa wakubwa?“ Walikubaliana upesi, na kwa pamoja, walibeba lile jiwe na kulirudisha mahali lilipokuwa mwanzo na kulificha karibu na kibanda chao cha kulala. Bila shaka, haikubaki siri kwa muda mrefu. Hata hivyo, walikuwa wamelihifadhi kwa ajili ya wenzao, ambao sasa walikuwa wakifanya mazoezi ya nguvu kadiri walivyokua kiumri.

Jiwe lilikaa eneo la wazi karibu na kanisa kwa takribani miongo miwili hadi vijana chipukizi walipolibeba na kulipeleka kwenye uwanja wao wa michezo na kulifanyia mazoezi huko. Lakini hilo halikumpendeza mtu mmoja ambaye wakati fulani alilitunza sehemu salama alipokuwa bado kijana. Siku moja, jiwe lilitoweka tena. Nilipochunguza lilipo, mtu huyu alijitokeza na kunijulisha kwamba amelihifadhi jiwe nyumbani kwake. Lakini halikuruhusiwa kurudi kwenye uwanja wa michezo. Vinginevyo, isingechukua muda mrefu kabla ya kupotea kabisa. Nilielewa hili na kumwachia jiwe kwa muda huo. Lakini ilikuwa muhimu kwangu kulihifadhi kwa vizazi vijavyo na sayansi. Fursa ya kufanya hivyo ilijitokeza kwangu ilipohitajika na mchango wa ukarimu uliwezesha ukarabati wa kanisa la zamani.

Pembe ya kaskazini-mashariki ya kwaya ilikuwa katika hatari ya kuanguka. Ilitokea kwamba wajenzii wa wakati huo walikuwa wameweka jiwe juu ya jiwe bila kuyaunganisha kwa upande wowote. Kwa kuzingatia hali ya jengo hilo, haikuwa vyema kuangusha kona hii na kuijenga upya. Bali, ili kulipa jengo zima usalama zaidi, usaidizi wa kipekee ulitakiwa kwa njia ya kujenga ukuta wa kudumu.

Hata hivyo, ukuta huu wa kudumu ulibadilika kuwa mnara wa ukumbusho wa ushindi. Kipande kilichoandikwa „Yesu ni Mshindi“ kiliwekwa juu ya msingi mkubwa wa saruji. Na juu yake kulikuwa na kipande cha jiwe la kusagia la Wachagga. Pia, juu ya kipande hiki ulikaa msalaba wa saruji, ambao ulishikilia ukuta hadi kwenye paa.

Kitako cha msalaba huu kilikuwa juu ya jiwe la kipagani, ambalo hatimaye lilipata mahali pake pa kupumzika. Hapa, jumuiya ya Mungu ilionyeshwa kwamba kipindi fulani waliongozwa kwa mawe yaliyokufa lakini sasa wanamtumikia Mungu aliye hai. Hata hivyo, kama jiwe la fuvu, anawakilisha asili yote ya mwanadamu kama ilivyofaradhishwa na kifo tangu Adamu. Msalaba unasimama juu yake na unamkiri yule aliyechukua nguvu za mauti na kuleta kiumbe cha milele kwenye nuru kwa ufufuo. Yesu ndiye mshindi na pia amelifunua jiwe hili la kipagani ili hamu ya maisha thabiti, safi na yenye kuzaa matunda, ambayo hapo awali ilishikamana nayo, sasa ipate utimilifu wa kweli juu yake na kuelekezwa kwenye huduma ya uzao wa kweli.

1 Using the word wapagani demeans the meaning and essence of the chagga in this stone, shared across Kilimanjaro. Publishing it as it means perpetuating Eurocentric ethno philosophy. What do you think?

Translation into Swahili by Dr Valence Silayo, [copy editing: ].