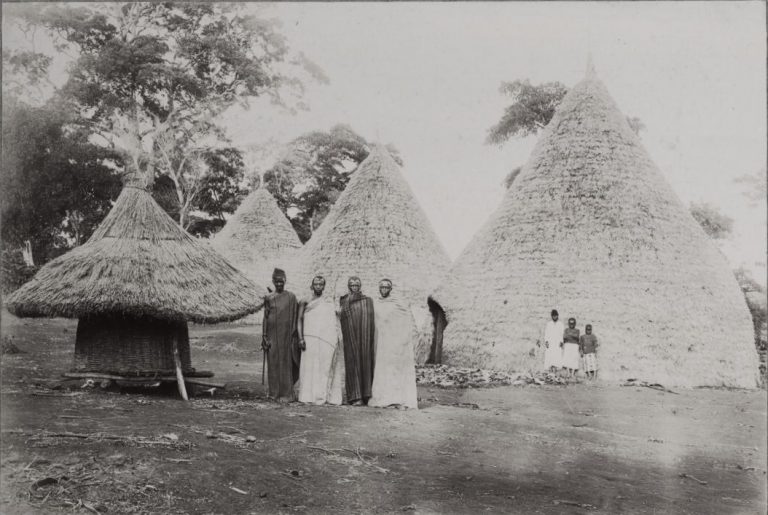

häuptling rindi - chief rindi

Häuptling Rindi von Moschimangi rindi from moshi

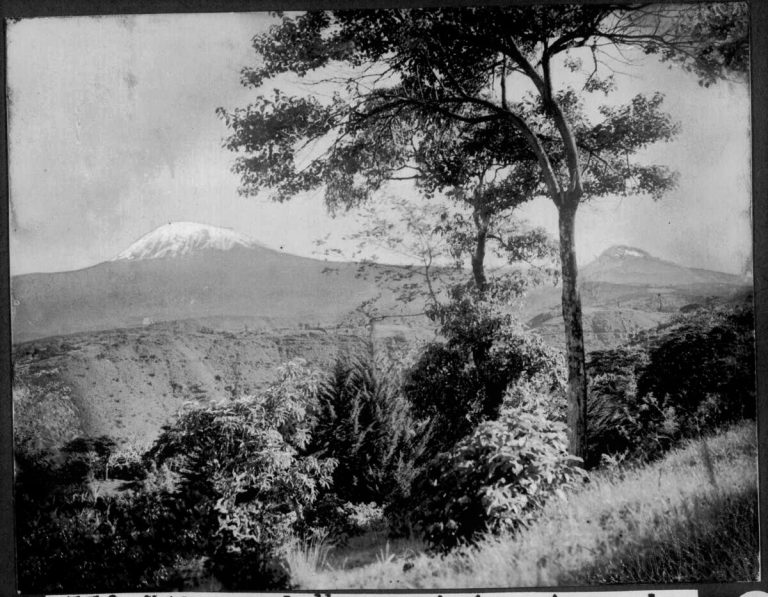

An important example of ‚writing‘ history based on orally transmitted sources is Gutmanns biography: Häuptling Rindi von Moschi, ein afrikanisches Helden- und Herrscherleben (Mangi Rindi of Moshi, the life of an African hero and ruler). This biography is a unique attempt to describe the life of an African leader on the eve of colonial conquest. Unlike accounts by explorers and later missionaries and military officers, who give no more than incidental anecdotes, Gutmann takes as his starting point carefully researched eyewitness accounts and the handed-down oral tradition. He traces the whole life, from birth to death, also describes the defeats and backlashes and does not leave out the problematic, less sympathetic sides of this leader’s personality. Although the person of Mangi Rindi is the main focus, the book also provides a lot of valuable and fascinating insights into the life of the Wachagga, their everyday life, culture and social interaction in the pre-colonial times.

The biography was published in German in 1928 in the then very popular series of the Schaffsteins grüne Bändchen in Cologne.

It stands here in a very special context of political biographies (Freiherr vom Stein, Napoleon I, Fürst Bismark, Charlemagne and other great rulers), descriptions of voyages of discovery and reports glorifying militarism.

In his Rindi biography, Gutmann’s writing style is very special: he uses many old and unusual words and grammatical constructions. He tried to write it like an old German heroic epic. Probably, he was inspired by the old German heroic sagas, and perhaps also by the Greek heroic sagas of classical antiquity. These writings, were very popular at the time (see for example the book by Gustav Schwab Sagen des klassischen Altertums, (Sagas of Classical Antiquity), published in 1840). Of course, it is also about information, but he writes of Mangi Rindi as a poet and singer who uses his songs to communicate with his people. Many of these songs are reported in the book and here Gutmann writes also in a very particular and ancient German in an attempt to translate these songs into German. For this purpose, he edited the texts, albeit only slightly. (See also below: songs.) Although Gutmann certainly did not develop this style of writing without ulterior motives, it was unfortunately not possible, and perhaps also not desirable, for the translations to take up these linguistic peculiarities and find appropriate wordings.

Below you can find additional material about this book (you can use the menu below to navigate directly to it).

In addition to pictures, these are mainly texts by Gutmann from other publications that he uses in this biography. At the beginning of each section you will find the page number of the biography to which the additional material refers.

menu

To find a topic or abstract more easily, you can use the key combination „CTRL + F“ (Win) or „CMD + F“ (Mac) to search for keywords or paragraphs within the pdf version of the book.

You can also copy text directly from the PDF file.

Note: It might be helpful to download the file because some browsers might struggle with this feature.

books

german (original)

view online:

english

coming soon

swahili

view online:

pictures

The illustration on the original cover of the book does not show Mangi Rindi, but his rival and enemy Mangi Marealle of Marangu (see also the reference on p. 6).

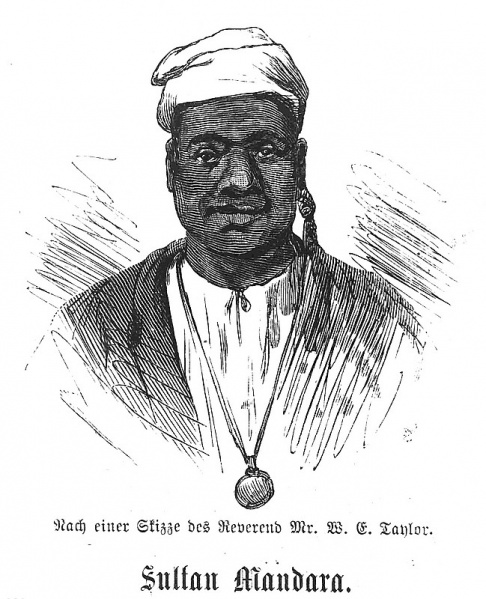

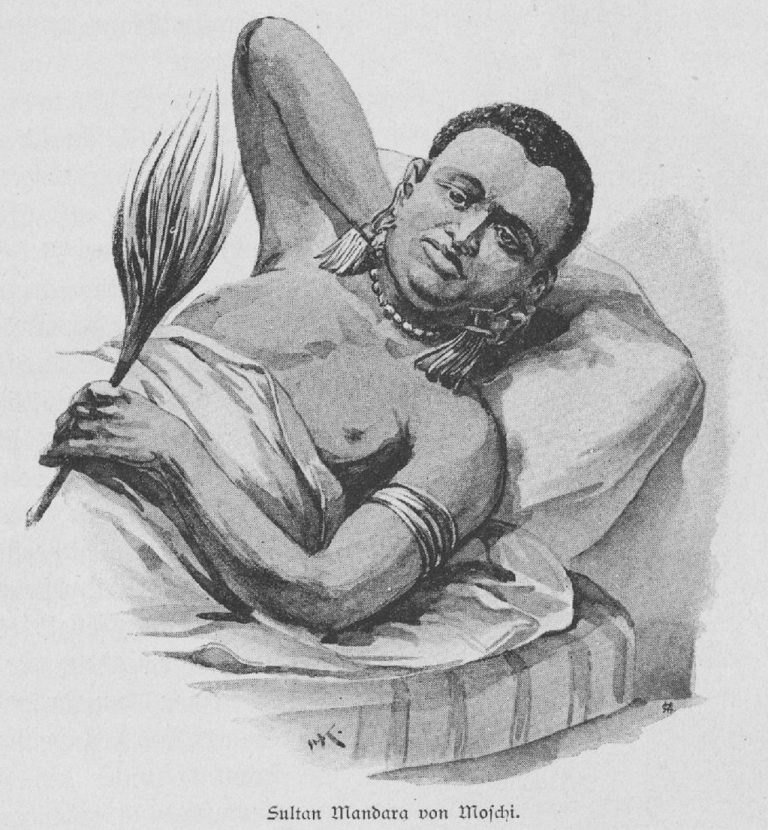

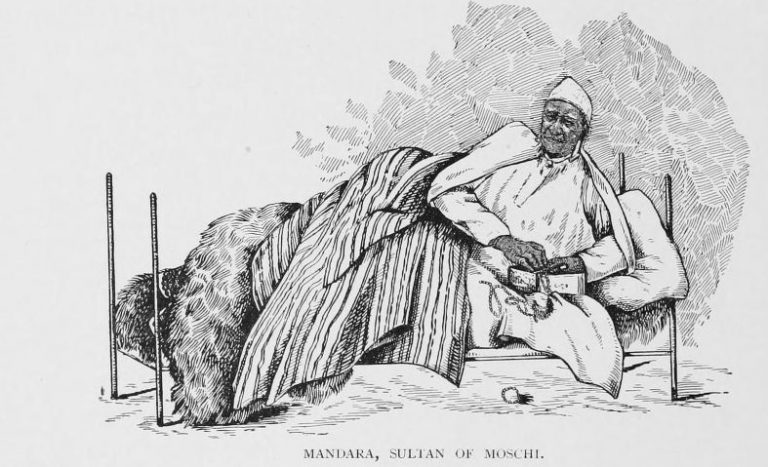

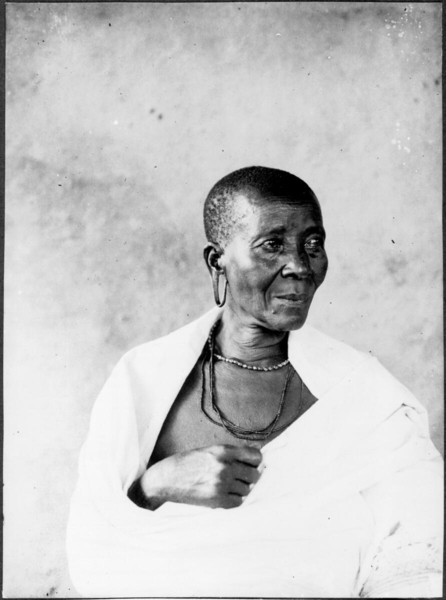

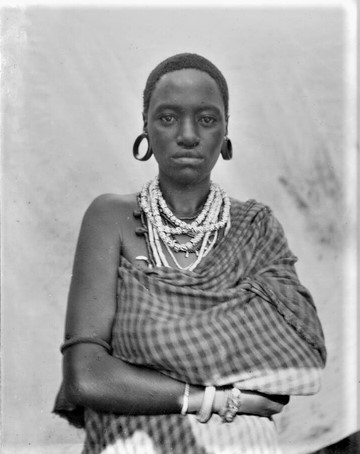

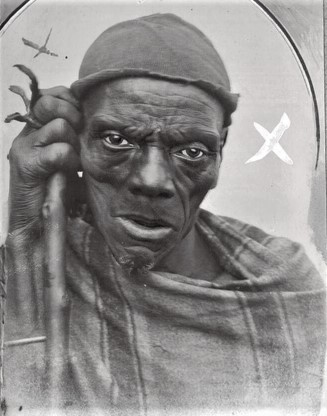

Until his death, Mangi Rindi always refused to be photographed. However, some missionaries and explorers made pen and ink drawings of very different quality of him during their visits.

songs

Three songs from the Rindi biography are also handed down by B. Gutmann in „The Songs of the Wachagga“ with the original Kichagga text. This is important because the comparison of the versions allows us to draw conclusions about the authenticity or adaptation of the other songs. In the preface to „Die Lieder der Dschagga“, he shows the rules according to which the pre-colonial Wachagga poetry was structured: for example, literal repetitions in the double verses and variants in the final word are important.

This can be understood very well in the original Kichagga texts. If we now compare the versions, it is noticeable that Gutmann adheres to these rules as far as possible in his translations in „Die Lieder der Dschagga“, and so did I in my translations into English. In the Rindi biography, he edits the songs (albeit only a little) to make them more varied in a „European“ sense. These edits can easily be found in a direct comparison of the two versions. Basically, however, the versions in the biography do not seem to be free adaptations, but rather fairly close to the original.

Translations into English by Hartmut Andres, [additions in square brackets].

Translations into Swahili: Dr Valence Silayo /Mr Ndesumbuka Merinyo.

Mangi Rindi of Moshi, page 46

Version from the Rindi Biography:

ORIGINAL

GERMAN

„Zwang ist’s, der Zwänger, der uns zwingt!

Und sterben wir, so soll doch Nachwuchs bleiben.

Und sterben wir, so sterben wir ihrer zwei!“

ENGLISH

„It is compulsion, the compulsor, that compels us!

And if we die, there shall still be offspring.

And if we die, we die together [we’ll both die]!“

SWAHILI

„Imetulazimu, mlazimishaji, katulazimisha kufanya!

Na tukifa, bado tutaacha uzao wetu.

Na tukifa, tunakufa pamoja (tutakufa nae)!“

Lieder der Dschagga: 11. Klagelied der Altersklasse Mirišo über den Zwang

Songs of the Wachagga: 11. Lament of the Mirišo age class about the compulsion

Oijē ojo lele ho!

Mkoromu mkorome folukoroma fo masumba.

Jē jē olele mkoromu fo masumba.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Mkoromu mkorome folukoroma fo wasuri.

Jē jē olele mkoromu fo wasuri.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Ho olele lukafa, lude luwa!

Ho olele lukafa lufe luwavi!

Jē jē olele mkoromu fo wasuri!

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Oijē ojo lele ho!

Zwang, der gezwungene zwingt uns von den Fürsten.

Jē jē olele, Zwang von den Fürsten.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Zwang, der gezwungene zwingt uns von den Reichen.

Jē jē olele, Zwang von den Reichen.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Ho olele sterben wir gleich, wir lassen Nachwuchs!

Ho olele sterben wir gleich, so sterben wir ihrer zwei!

Jē jē olele, Zwang von den Reichen.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Oijē ojo lele ho!

Compulsion, the compelled compels us from the princes.

Jē jē olele, compulsion from the princes.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahá!

Compulsion, the compelled compels us from the rich.

Jē jē olele, compulsion from the rich.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

Ho olele [if] we’re going to die, we’re leaving offspring!

Ho olele [if] we’re going to die, we die together [we’ll both die]!

Jē jē olele, compulsion from the rich.

Haja haja há! Hije hajahahá!

coming soon

Mangi Rindi of Moshi, page 53

Version from the Rindi Biography:

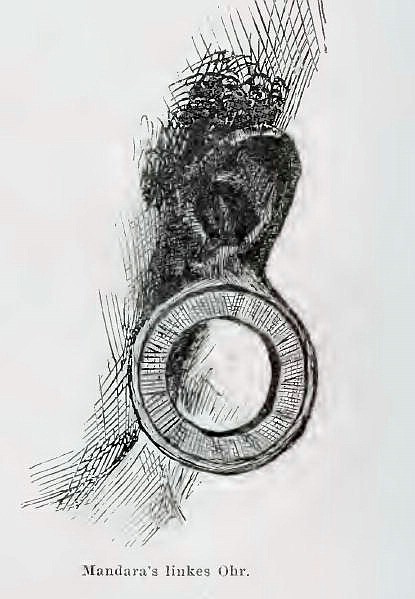

„Der Mann der Scheibe ist wiedergekommen,

der Mann, dem der Ohrpflock stolz über die Schulter steht.

Ojahe ohehehe, hia hajaja!

„Der Mann der Scheibe“: Rindi trug eine große Ohrscheibe.

„The man ofwith the disc“: Rindi wore a large ear disc.

Mwanaume mwenye ndonya amerudi,

mwanaume ambaye vigingi vyake vya masikio husimama kwa majivuno juu ya mabega yake.

Ojahe ohehe, hia hajaja!

Mangi Rindi of Moshi, page 57

Version from the Rindi Biography:

.

„Laßt uns den Stecken entrinden, laßt uns den Stein behaun.

Ratsherren wollen wir daraus machen, ob wir zur Größe kommen möchten wie früher.

Und müßten wir sie aus der Erde graben!

Ho Stecken, ho Stein! Häuptling Rindi ist klug genug andere zu lehren!

Hab ich doch den Tere-Tere*) gehobelt und zum Ratsherrn gemacht.

Ich schnitzte den Stecken, zum Ratsherrn hab ich ihn gemacht.

Ich stellte ihn aufrecht, und er verwandelte sich in einen Menschen.

O Stecken, o Stein!

Ich behaute den Stein, ich machte ihn zu einem Menschen,

den Stein, der nicht reden konnte.“

*) einen Madschamemann

„Let us bark [strip the bark from] the stick, let us hew the stone.

Let us make councilors out of them, whether we would achieve greatness as in the past.

And if we would have to dig them out of the ground!

Ho stick, ho stone! Chief Rindi is wise enough to teach others!

But I have planed the Tere-Tere*) and made him a councilor.

I carved the stick, I made him a councilor.

I set it upright and it turned into a human being.

O stick, o stone!

I hewed the stone, I made it into human being,

the stone that could not speak.“

*) a Machame man

Hebu tuchonge fimbo, tuchonge jiwe

Tumfanye diwani

Kama hatutapata ukuu wetu kama zamani.

Hata ikibidi kumchimbua kutoka ardhini!

Ho fimbo, ho jiwe! Mangi Rindi ana hekima ya kutosha, Kufundisha wengine pia.

Nilimgawanya Tere-Tere; Nilimgeuza kuwa diwani.

Nilichonga fimbo; nikaigeuza kuwa diwani.

Niliiweka sehemu, na aligeuka kuwa binadamu.

Ho fimbo, ho jiwe!

Nilichonga jiwe, nikalifanya kuwa mwanadamu,

Jiwe ambalo halikuweza kuongea!

Lieder der Dschagga: 10. Häuptling Rindis Lied: Selbstermunterung zur Erziehung seiner Männer

Songs of the Wachagga: 10. Mangi Rindi’s song: self-encouragement to educate his men

Lupatše kidi, lupatše kiho,

Luhaluo nžama!

Kulako noi̇ṅana tša katša.

Kiti luisuma wanda!

Ho kidi, ho kiho,

Mangi Rindi ni mrango mnu,

Karanguja vengi,

Ngapara Tere-tere ngahaluo ndžama.

Ngapatša kidi ngahaluo ndžama.

Ngahorotsa hando kikahaluka mndu.

Ho kidi, ho kiho.

Ngapatša kiho ngahaluo mndo –

Kiho kilēdeda!

Lasst uns den Stock beschnitzen, lasst uns den Stein behaun

Zum Ratsherrn wolln wir ihn machen!

Ob wir nicht hochkommen wie einst.

Und müßten wir ihn aus der Erde graben!

Ho Stock, ho Stein,

Häuptling Rindi ist klug genug,

Auch andere klug zu machen.

Ich spaltete den Tere-tere auf, ich wandelte ihn zum Ratsherrn.

Ich beschnitzte den Stock, ich wandelte ihn zum Ratsherrn.

Ich pflanzte ihn auf an einer Stelle, und er verwandelte sich in einen Menschen.

Ho Stock, ho Stein.

Ich behaute den Stein und machte ihn zu einem Menschen

Den Stein, der nicht reden konnte!

Let us carve the stick, let us carve [hew] the stone,

Let’s make him a councilor!

Whether we do not rise as we once did.

And if we would have to dig him out of the ground!

Ho, stick; ho, stone!

Mangi Rindi is wise enough,

To make others wise too.

I split the Tere-tere, I transformed him into a councillor.

I carved the stick, I transformed it into a councillor.

I set it up in a place, and he transformed into a human being.

Ho, stick; ho, stone!

I carved [hewed] the stone and made it a human being.

The stone that could not speak!

Hebu tuchonge fimbo, tuchonge jiwe,

Tumfanye diwani

Kama hatutapata ukuu wetu kama zamani.

Hata ikibidi kumchimbua kutoka ardhini!

Ho fimbo, ho jiwe!

Mangi Rindi ana hekima ya kutosha,

Kufundisha wengine pia

Nilimgawanya Tere-Tere;

Nilimgeuza kuwa diwani.

Nilichonga fimbo; nikaigeuza kuwa diwani.

Niliiweka sehemu, na aligeuka kuwa binadamu.

Ho fimbo, ho jiwe!

Nilichonga jiwe, nikalifanya kuwa mwanadamu,

Jiwe ambalo halikuweza kuongea!

Mangi Rindi of Moshi, page 76

Version from the Rindi Biography:

.

„Wehe mir, wehe mir! Das ist mein Schicksal ihr Männer!

Ich sehe den Stier geschlachtet, ihr Helden!

Ich sehe das Leid zurückgelassen aus seiner Haut.

Die Haut wird ausgespannt werden mit Pflöcken.

Die Haut wird ausgespannt werden wie eine Amulettechse.

Zu Häuptling Tetia bin ich einst geflüchtet,

dann sagte man mir: er ist gestorben.

Zu meiner Mutter flüchtete ich, der trauten, die sich um mich mühte, die Holde.

Dann sagte man mir: Matschaki ist nun auch tot!

Nun fehlt mir, bei dem ich weinen könnte in meinem Leide.

Nun weiß ich keinen mehr, dem ich so meine Trübsal klagen darf.

Nun klage ich euch, ihr meine Alten.

Vor euch klage ich Trübsal und Not.

Nun helft mir, das Leid zu beweinen.

Mein ist die Bedrängnis jetzt, an mir haftet das Weh.

Aber ich sehe voraus: es wird das eure.

Ich verlasse mein Heim, euch bleibt die Not.“

„Woe to me, woe to me! This is my fate, you men!

I see the bull slaughtered, you heroes!

I see the grief left behind from his skin.

The skin will be stretched out with pegs.

The skin will be stretched out like an amulet lizard.

To chief Ndetia I once fled,

Then they told me he had died.

To my mother I fled, the gentle one who cared for me, the fair one.

Then I was told: Machaki is now dead too!

Now I have no one to cry to in my grief.

Now I know no one to whom I may lament my sorrow.

Now I lament to you, my elders.

Before you I lament my sorrow and distress.

Now help me to cry about my grief.

Affliction is now mine, and woe sticks to me.

But I foresee: it will be yours.

I leave my home, distress will remain to you.“

“Ole wangu, ole wangu!

Hii ndio hatima yangu, enyi watu

Namuona fahali akichinjwa, enyi mashujaa!

Najua huzuni inayoachwa kwenye ngozi yake.

Ngozi yake itawambwa kwa vigingi.

Ngozi yake itavutwa kama ya mjusi.

Niliwahi kukimbilia kwa mangi Ndetea,

Kisha nikaambiwa amefariki.

Nilikimbilia kwa mama yangu, yule mpole, aliyenijali, na mwenye haki.

Kisha nikaambiwa: Mamchaki amefariki pia!

Sasa, sina mtu wa kumlilia katika huzuni yangu.

Sasa, sijui mtu yeyote wa kumweleza huzuni yangu.

Sasa nitaomboleza kwenu wazee wangu.

Mbele yenu, ninaomboleza huzuni na dhiki yangu.

Nisaidieni kulia na kuomboleza huzuni yangu.

Taabu ni yangu, huzuni imeniganda.

Lakini nina maono kuwa itabaki kwenu.

Ninaondoka nyumbani kwangu, nanyi mtabaki na taabu.”

Lieder der Dschagga: 12. Häuptling Rindis Klagelied über sein Sterben

Songs of the Wachagga: 12. Mangi Rindi’s lament about his death [facing his appoaching death]

Otšiań, otšiani loko, lanje, wasoro!

Ndžiwoń puṅa jašindžo, warori wako!

Ndžiwoń wukiwa wodeo tšonihu.

Tšońi jetšikapyo mambo,

Tšońi jetšikapyo mambo tša ikuti.

Ngawuja mangi Tetia ngaitšo lemfa,

Ngawuja mai oko Tongito, Tonga lae,

Ngamitšo Mkatšaki-le lemfa.

Ngawura mofuhya wukiwa.

Ndžilamanje mndu ngamhuhya-se wukiwa.

Wulala ngafuhya wameku wako,

Niwo ngalia wale woko,

Niwo ngalia wukiwa woko.

Wulalu mundžyeke ifuha unjanti woko,

Wulalu mundžyeke ifuha otšini loko!

Ngawona wale wotšiwa wonu,

Ngamda kań wukiwa, wowa wonu.

Wehe, wehe mir, ihr Männer!

Ich sehe, der Stier wird gehäutet, meine Helden!

Ich sehe dieTrübsal bleibt zurück auf dem Fell.

Das Fell wird ausgeschlagen mit Pflöcken,

Das Fell wird festgepflöckt, wie ein Waran.

Ich kehrte um zu Häuptling Tetia, da hörte ich: „Ist längst gestorben.“

Ich kehrte um zu meiner Mutter, der Holdseligen, der Holden,

Ich hörte von der Frau der Tšaki-Sippe: „Längst gestorben.“

Nun fehlt mir, dem ich Trübsal sagen könnte.

Keinen weiß ich mehr, dem ich die Trübsal klagen könnte.

Nun klage ich meinen Alten.

Ihnen weine ich meine Not.

Ihnen weine ich meine Trübsal.

Nun helft mir mein Unheil beklagen,

Nun helft mir mein Wehe beklagen!

Ich sehe, die Not wird euch verbleiben.

Hab ich das Heim verlassen, verbleibt euch das Unglück.

Woe, woe to me, you men!

I see the bull is flayed, my heroes!

I see the sorrow remains on the hide.

The hide will be streched out with pegs,

The hide will be pegged, like a monitor lizard.

I turned back to Mangi Ndetia, then I heard, „Has

died long ago.“

I turned back to my mother, the fair and blessed, the fair one,

I heard about the woman of the Tšaki clan, „Died long ago.“

Now I have no one to whom I can tell my sorrow.

There is no one left to whom I can lament my sorrow.

Now I lament to my elders.

To them I cry my distress.

To them I cry my sorrow.

Now help me lament my misery,

Now help me lament my woe!

I see that the distress will remain with you.

When I have left the home, misfortune will remain with you.

“Ole, ole wangu, enyi watu!

Namuona fahali akichinjwa, mashujaa wangu!

Naona huzuni inabaki kwenye ngozi yake.

Ngozi yake itawambwa kwa vigingi.

Manyoya yatavutwa, kama kenge.

Nilikimbilia kwa Mangi Ndetea,

Kisha nikasikia, „Amefariki zamani“.

Nikarudi kwa mama yangu, yule mpole aliyebarikiwa, na mwenye haki.

Nilisikia habari za mwanamke wa ukoo wa Tshaki,

„Alikufa zamani.“

Sasa, sina mtu wa kumweleza huzuni yangu.

Hakuna mtu yeyote aliyebakia wa kumweleza huzuni yangu.

Sasa ninaomboleza kwa wazee wangu.

Kwao, ninalia dhiki yangu.

Kwao, ninaomboleza huzuni yangu.

Sasa nisaidie kuomboleza taabu zangu!

Sasa nisaidie kuomboleza huzuni yangu

Nona dhiki itabaki kwenu.

Nitakapokuwa nimeondoka nyumbani, mabalaa yatabaki nanyi.

stories

p. 47/48

Version from the Rindi Biography:

Sie erzählen von mancherlei Warnungszeichen, die dem Zuge vorausgegangen seien. Eine Beutekuh aus Useri habe mit Menschenstimme ein Klagelied gesungen. Als sie deshalb geschlachtet worden war, sei sie nach der Abhäutung wieder aufgestanden, eine Strecke fortgelaufen und dann erst stöhnend zusammengesunken. (S. 47)

Einen Vornehmen namens Mana Tschuwa, der zu Hause geblieben war, zwang Rindi selbst, den Männern nachzugehen. Der soll unterwegs mehreren Kriegern begegnet sein, die sich nach Hause schlichen, und sie niedergestoßen haben. (S.48)

Gutmann gibt im “Volksbuch der Wadschagga“ folgende Erzählung:

18. Das Lied der Kuh.

Der Häuptling Rindi von Moschi ließ einen Kriegszug nach Kireri unternehmen. Das sind die Landschaften von Mamba bis Tšimbi. Mit vielen Rindern kamen die Krieger zurück. Der Häuptling verteilte die Beute. Mtana Tšuwa, ein angesehener Totschläger, bekam zwei schöne Rinder. Er führte sie in sein Haus und legte ihnen Gras vor. Sie schnoben darüber hin, fraßen aber nichts. Das beste Gras brachte er – sie schnoben und rührten nichts an. Auch vom Wasser tranken sie nicht. Am anderen Tag gingen alle Hofgenossen zur Steppe auf die Maisäcker, denn der Häuptling achtete daruf, daß sie fleißig ackerten. Nur ein Mädchen blieb zu Hause bei Mtana. Das hörte plötzlich ein Lied im Hause singen:

„Ho Rile, was für Gräser soll ich fressen!

Ho Rile warum hast du mich aus Kireri weggetan

Und hierher zu dem Mtana der Watšuwa?

Gräser die mir wohlbekamen, sind das Ng’arogras,

Sind die Tescho-, Pfundopfundo-, Mhuhugräser!

Die sind schön!

Und das Wasser, das ich trinke, ist vom Ngasibache.

Vom Mawentsi strömt es nieder,

Aus den Klüften des Kibo.

Hierher hast du mich nun gebracht.

Legst mir vor vom Fettkraut1 und vom Taugras1 –

Nicht fressen mag ich’s!

Trinken soll ich das Wasser, erdig trübe –

Nicht trinken mag ich’s!

Ho Rile, was für Gräser soll ich fressen!

Warum hast du mich von Kireri weggetan

Und hierher zu dem Mtana der Watšuwa?“

1 vermutlich Grassorten wie Zeile 4 und 5, die ich aber nicht identifizieren kann.

Das Mädchen horchte und staunte. War doch kein Mensch im Hause. Sie schlich sich heran und öffnete leise die Tür und hörte die Rinder singen. Das andere Rind sang immer dazwischen: „E hehohi ho Rile.“

Mtana sprach: „Es ist eine Lüge“, als ihm das Mädchen davon berichtete. Er ging leise hinzu und hörte es auch. Rindi, der Häuptling, wollte es auch nicht glauben. Er kam und hörte das Lied. Da sprach er: „Das Rind muß geschlachtet werden!“ Mtana antwortete: „Mag davon essen, wer will. Ich mag nichts von einem Rinde, das da redet wie ein Mensch!“ Und er gab es den Männern, die mußten es von seinem Hofe führen. Sie schlachteten es im Gebüsch. Als sie ihm aber das Fell abgezogen hatten, richtete es sich noch einmal auf und brüllte „ṅa!“

Da wich ein Teil dieser Männer. Sie sprachen: „Wer mag von diesem Fleisch essen?“

Im anderen Jahre ließ Rindi seine Männer wieder gegen Oseri ziehen. Mtana Tšuwa aber blieb zu Hause. Er sprach: „Ich gehe nicht wieder mit ins Land der redenden Rinder.“ Doch der Häuptling geriet in Zorn, als er ihn noch im Lande sah, und sprach zu ihm: „Gehst du nicht dem Heerzuge nach, dann jage ich dich in die Fremde!“ Da ging Mtana mit seinen Männern dem Kriegerzuge nach über den Urwald. Unterwegs begegneten ihm Krieger, die sich heimschleichen wollten. Er stach sie nieder und erreichte den Haufen. Zwei lang verheerten sie die Oserilandschaften. Am dritten Tage aber begann die Erde zu zittern und zu dröhnen: wuwuwu. Die Männer erschraken und flohen. Auf die Fliehenden warfen sich die Männer in allen Landschaften. Auch Mtana fiel. Auf einen Tag verlor Rindi alle seine Krieger.

Und er gedachte wieder an das Lied der Kuh und sang es oft vor seinen Kindern.

p. 47/48

Version from the Rindi Biography:

They tell of various warning signs that preceded the campaign.

A prey cow from Useri had sung a lament in a human voice.

When it had been slaughtered for this reason, it got up again after skinning, walked a distance and then slumped down with a groan. (P. 47)

Rindi himself forced a nobleman called Mana O Chuwa, who had stayed at home, to follow the men. He is said to have met several warriors on the way, who sneaked home and struck them down. (P. 48)

Gutmann gives the following story in the „Volksbuch der Wadschagga“:

18. The song of the cow.

The chief Rindi of Moschi ordered a war campaign to Kireri. These are the landscapes from Mamba to Tšimbi. The warriors returned with many cattle. The chief distributed the booty. Mtana Tšuwa, a respected manslayer, got two beautiful cattle. He led them into his house and put grass before them. They snorted at it, but ate nothing. He brought the best grass – they snorted and touched nothing. Nor did they drink of the water. The next day, all the farm members went to the maize fields on the steppe, because the chief made sure that they worked industriously. Only one girl stayed at home with Mtana. Suddenly she heard a song singing in the house:

„Ho Rile, what grasses shall I eat!

Ho Rile, why have you taken me away from Kireri?

And here to the Mtana of the Watšuwa?

Grasses that have been good to me are the Ng’arograss,

Are the Tescho-, Pfundopfundo-, Mhuhugrasses!

They are fine!

And the water I drink is from the Ngasistream.

From the Mawentsi it flows down,

From the gorges of Kibo.

Here you have brought me.

You put before me of the fat weed1 and the dew grass1 –

I don’t want to eat it!

I shall drink the water, earthy murky –

I will not drink it!

Ho Rile, what grasses shall I eat!

Why did you take me away from Kireri

And here to the Mtana of the Watšuwa?“

1 probably grass species like in lines 4 and 5, but I cannot identify them.

The girl listened and was astonished [wondered]. There was no one in the house. She sneaked up and quietly opened the door and heard the cattle singing. The other cow kept singing in between: „E hehohi ho Rile.“

Mtana said, „It is a lie,“ when the girl told him about it. He went quietly and heard it too. Rindi, the chief, did not want to believe it either. He came and heard the song. Then he said, „The ox must be slaughtered!“ Mtana answered: „Whoever wants to eat it, may do so. I don’t like anything from an ox that talks like a man!“ And he gave it to the men, who had to lead it from his court. They slaughtered it in the bushes. But when they had stripped it of its skin, it reared up once more and roared, „ṅa!“

Then some of these men backed way. They said, „Who may eat of this meat?“

The next year, Rindi sent his men against Oseri again. Mtana Tšuwa, however, stayed at home. He said, „I will not go back to the land of the talking cattle.“ But the chief, when he saw him still in the country, became angry and said to him, „If you do not go with the army, I will chase you abroad [into a foreign land]!“ So Mtana and his men followed the warriors‘ march across the mountain forest. On the way he met warriors who wanted to sneak home. He stabbed them and reached the troop. For two days they devastated the Oseri lands. But on the third day the earth began to tremble and roar: wuwuwu. The men were terrified and fled. The men from all the landscapes lunged at the fleeing men. Mtana also died. In one day Rindi lost all his warriors.

And he remembered the song of the cow again and often sang it before his children.

Translation into English by Hartmut Andres, [additions in square brackets].

p. 47/48

Version from the Rindi Biography:

Kwa maneno ya mwisho, walionyesha kwamba uharibifu wa rika ulimaanisha pia anguko la mangi. Zinasemwa ishara mbalimbali za maonyo zilizotangulia kampeni hii. Ng’ombe aliyechukuliwa Useri aliimba wimbo wa maombolezo kwa sauti ya mwanadamu. Baada ya kuchinjwa, alinyanyuka tena baada ya kuchunwa ngozi, akatembea umbali fulani kisha akadondoka chini huku akikoroma.

Wapiganaji wa Moshi walifuata njia inayopitia nyanda za juu za mlima. Rindi alimlazimisha mtu aliyeitwa Mana O Chuwa, ambaye alikuwa amebaki nyumbani, kuwafuata wanaume hao. Inasemekana alikutana na wapiganaji kadhaa njiani, ambao walitoroka kwa siri kurudi nyumbani, akawachoma mikuki.

Gutmann anatoa hadithi ifuatayo katika, “Volksbuch der Wadschagga”:

18. Wimbo wa ng’ombe.

Mangi Rindi wa Moshi aliamuru kampeni ya vita dhidi ya Kireri. Haya ni mandhari kutoka Mamba hadi Tšimbi. Wanajeshi walirudi na ng’ombe wengi. Mangi aligawa nyara. Mtana Tšuwa, mwuaji anayeheshimika, alipata ng’ombe wawili wazuri. Aliwaingiza nyumbani kwake na kuweka majani mbele yao. Walikwaruza pua zao lakini hawakula chochote. Akaleta majani bora zaidi – walikwaruza lakini hawakugusa chochote. Hawakunywa hata maji. Siku iliyofuata, watu wote wa shamba walienda kwenye mashamba ya mahindi kwenye tambarare, kwa sababu Mangi alihakikisha kwamba walifanya kazi kwa bidii. Ni msichana mmoja tu aliyebaki nyumbani na Mtana. Ghafla alisikia wimbo ukiimbwa ndani ya nyumba:

„Ho Rile, majani gani nitakula!

Ho Rile, kwa nini umenitoa Kireri?

Na hapa kwa Mtana wa Watšuwa? Majani yaliyonifaa ni ya ng’aro,

Ni ya tesho, pfundopfundo, mhuhu!

Ni mazuri! Na maji ninayokunywa ni ya kijito cha Ngasi.

Kutoka Mawenzi yanatiririka chini,

Kutoka korongo za Kibo.

Hapa umenileta.

Umeniwekea mbele yangu majani ya mafuta1 na nyasi za umande1 –

Sitaki kuyala!

Ntakunywa maji ya udongo yenye tope –

Sitaki kuyanywa!

Ho Rile, majani gani nitakula!

Kwa nini umenitoa Kireri

Na hapa kwa Mtana wa Watšuwa?“

1 Pengine aina za majani kama katika mistari ya 4 na 5, lakini siwezi kuzitambua.

Msichana alisikiliza na kushangaa. Hakukuwa na mtu ndani ya nyumba. Alijivuta kwa utulivu na kufungua mlango kimya kimya na kusikia ng’ombe wakiimba. Ng’ombe mwingine aliendelea kuimba mara kwa mara: „E hehohi ho Rile.“

Mtana alisema, „Ni uongo,“ msichana alipomwambia. Alienda kimya na kusikia pia. Rindi, Mangi, hakuwa na imani pia. Alikuja na kusikia wimbo. Kisha akasema, „Ng’ombe huyo lazima achinjwe!“ Mtana akajibu: „Anayetaka kula, na ale. Sipendi kitu chochote kutoka kwa ng’ombe anayezungumza kama mwanadamu!“ Na akawapa wanaume, ambao walimtoa kwenye korti yake. Walimchinja kichakani. Lakini walipomnyang’anya ngozi, alisimama tena na akanguruma, „ṅa!“

Kisha baadhi ya wanaume hao wakarudi nyuma. Walisema, „Nani atakula nyama hii?“

Mwaka uliofuata, Rindi alituma watu wake tena dhidi ya Oseri. Hata hivyo, Mtana Tšuwa alibaki nyumbani. Alisema, „Sitaki kurudi kwenye nchi ya ng’ombe wanaozungumza.“ Lakini Mangi, alipomwona bado yuko nchini, alikasirika na kumwambia, „Kama hutaenda na jeshi, nitakufukuza uhamishoni!“ Kwa hivyo Mtana na watu wake wakafuata maandamano ya wapiganaji kuvuka msitu wa mlima. Njiani alikutana na wanajeshi waliotaka kurudi nyumbani kwa siri. Aliwachoma visu na kufika kwenye kikosi. Kwa siku mbili waliharibu ardhi za Oseri. Lakini siku ya tatu ardhi ilianza kutetemeka na kunguruma: “wuwuwu”. Wanaume walishikwa na hofu na wakakimbia. Wanaume kutoka mandhari zote walivamia wanaume waliokuwa wakikimbia. Mtana pia alikufa. Kwa siku moja, Rindi alipoteza wapiganaji wake wote.

Na alikumbuka wimbo wa ng’ombe tena na mara nyingi aliimba mbele ya watoto wake.

Imetafsiriwa kutoka Kiingereza na Elisia Mandara.

p. 58

Version from the Rindi Biography:

Ansprechend sind besonders die Züge, die aus seinem Umgange mit den Kindern berichtet werden. Wie er sich zum Parteigänger jener Schar machte, die gegen seinen Sohn Meli kämpfte, wie er sie in einer Hungersnot vor den Versuchungen zum Stehlen warnte und sie zu sich einlud, wenn es daheim nichts zu essen gäbe. (Seite 58)

Gutmann gibt im „Recht der Dschagga“ die folgende sehr lebendige Erinnerung von Petro Masamu an Mangi Rindi (vermutlich aus dem Jahr 1884/85):

„Ma mlaive: ihr sollt nicht stehlen!“

„Als die Teuerung sehr groß wurde, begannen Leute aus Mangel zu sterben. Da befahl Häuptling Rindi, auf den Höfen zu schlachten zu Bezirksspeisungen, jeder Große ein Rind, jeder Arme ein Stück Kleinvieh. Als das Kleinvieh zu Ende ging, befahl er: „Jeder Erwachsene komme nun zum Häuptling.“

Von da an begann er Tag für Tag Rinder zu schlachten, die in Uhonu erbeutet worden waren. Die Männer ließen darum die Hausvorräte den Kindern und gingen selber zum Häuptlinge, sich dort zu

sättigen.

Aus diesen Tagen stammt meine Erinnerung an Häuptling Rindi: Ich hütete eines Tages die Ziegen, als mich der Hunger packte. Eilig trieb ich heim, fand aber nichts zu essen vor und die Mutter abwesend auf der Heische nach Dörrbananen. Mit dem Nachbarssohne trieb’s mich wieder davon. Wir gingen zwischen die Häuptlingsgehöfte. Es war am frühen Nachmittag. Wir sahen den Häuptling zwischen seinen Frauen sitzen und Fleisch essen. Und der voranstand, das war ich. Schüchtern hielt ich mich im Schatten zweier Häuser. Da sah er mich. Er war ganz nahe. Ich grüßte ihn, er antwortete nichts, und ich wagte es nicht mich zu setzen. Darnach fragte er mich: „Du, wessen Kind bist du?“ Ich sagte es ihm. Und weiter fragte er: „Was für Zeit?“ „Hunger, Herr!“ antwortete ich. Er schnitt nun von dem Fleische ab, das vor ihm lag und gab es mir mit den Worten: „Da nimm, mein Sohn!“ Ich ergriff es und dankte ihm. Er hieß mich niedersitzen und essen, gab mir auch sein Messer. Als die andern Kinder, die sich verborgen hielten, sahen, was mir widerfuhr, wagten sie sich auch heran. Ich hätte mein Fleisch gern nach Hause getragen, doch er befahl mir: „Sitze nieder und iß mit deinen Gefährten!“ So zehrten wir’s denn auf und wurden alle satt. Darnach befahl uns der Häuptling: „Salbt euch mit dem Fett!“ Wir salbten uns.

Währenddessen war er in Unterhaltung mit einem Suahelimanne begriffen, namens Mamdu.

Jetzt aber brach er das Gespräch mit ihm ab und wandte sich ganz zu uns. Und er sprach zu uns: „Was herrscht jetzt?“ „Der Hunger, Häuptling!“ Und euren Kameraden, wie geht es ihnen?“ „Sie sterben, Herr!“ „Ja, nehmt nur in Acht, wie man Steine auf sie wirft. Ihr sollt nicht stehlen.“ „Nein, Herr!“ „Ihr sollt nicht stehlen!“ „Nein, Herr!“ „Ihr sollt nicht stehlen!“ „Nein, Herr!“ „Wenn ihr stehlt, und sei es auch ein Vornehmer, so kann er sich nicht davor wahren, daß man ihm die Gelenke mit Steinen zerschlägt!“ „Nein, Herr!“ „Aber wenn ihr nicht stehlt, so sterbt ihr nicht. Wenn euch der Hunger recht weh tut, so eilt zum Häuptling und sammelt euch die Schnitzel vom Schlachtrasen der Männer. Fürchtet euch ja nicht hierherzukommen.“ Und diese Ansprache schloß er mit denselben Worten, mit denen er sonst den Männerrat zu beschließen pflegte: „Ruft hiwo!“ Und wir riefen: „Hiwo!“ „Geht heim, meine Knaben!“ „Ja Herr!“ „Gebt den Jubelruf!“ Und wir trillerten. Wir gingen aber heim, erfüllt mit großer Freude.

(Nach Petro Masamu)

Das Recht der Dschagga, S. 584/85 [578/79]

p. 58

Version from the Rindi Biography:

The traits that are reported from his interaction with the children are particularly appealing. How he made himself a partisan [supporter] of the group that fought against his son Meli, how he warned them during a famine of the temptation to steal and invited them to his house when there was nothing to eat at home. (Page 58)

Gutmann gives the following very vivid memory [recollection] of Mangi Rindi by Petro Masamu in „Das Recht der Dschagga“ (probably from the year 1884/85):

„Ma mlaive: you shall not steal!“

When the dearth became great, people began to die for lack of food. Then Mangi Rindi ordered the slaughtering of cattle on the homesteads for district feedings, each of the great [ones] a bull, each poor man a piece of small livestock.

From then on, he started day after day to slaughter cattle that had been captured in Uhonu. The men therefore left the household supplies to the children and went to the chief themselves to eat.

My memory of Mangi Rindi dates back to those days: I was herding the goats one day when I got hungry. I drove [them] home in a hurry, but found nothing to eat and my mother absent to beg for dried bananas.

I drifted away again with the neighbor’s son. We walked in between the chief’s homesteads. It was early afternoon. We saw the chief sitting between his wives and eating meat. And the one in front was me. I stood shyly in the shade of two houses.

Then he saw me. He was very close. I greeted him, he didn’t answer and I didn’t dare to sit down. Then he asked me: „You, whose child are you?“ I told him. And then he asked: „What kind of time?“ „Hunger, Lord!“ I replied. He then cut of the meat that was in front of him and gave it to me, saying: „Take this, my son!“ I took it and thanked him. He told me to sit down and eat and gave me his knife. When the other children, who had been hiding, saw what was happening to me, they also dared to approach.

I would have liked to carry my meat home, but he ordered me: „Sit down and eat with your companions!“ So we ate it and were all sated.

Then the chief commanded us: „Anoint yourselves with the fat!“ We anointed ourselves.

At the same time, he was in conversation with a Swahili man called Mamdu.

But now he terminated the conversation with him and completely turned to us. And he said to us: „What rules now?“ „Hunger, chief!“ And your comrades, how are they?“ „They are dying, Lord!“ „Yes, just beware [watch out] how stones are thrown at them. You should not steal.“ „No, Lord!“ „You shall not steal!“ „No, Lord!“ „You shall not steal!“ „No, Lord!“ „If you steal, even if it is a nobleman, he cannot save himself from having his joints smashed with stones!“ „No, Lord!“ „But if you don’t steal, you won’t die. If you are really hungry hurry to the chief and collect the scraps from the men’s slaughter lawn. Don’t be afraid to come here.“

And he concluded this speech with the same words with which he used to conclude the men’s council: „Shout hiwo!“ And we shouted: „Hiwo!“ „Go home, my boys!“ „Yes Lord!“ „Give the cheer!“

And we trilled. So we went home, filled with great joy.

„Das Recht der Dschagga“, PP. 584/85 [578/79]

Translation into English by Hartmut Andres, [additions in square brackets].

p. 58

Version from the Rindi Biography:

Kinachovutia zaidi ni sifa zilizotolewa kutokana na mapenzi yake kwa watoto. Jinsi alivyokuwa mlezi wa kikundi kilichopigana na mtoto wake Meli, jinsi alivyowaonya dhhidi ya majaribu ya kuiba wakati wa najaa, na kuwaalika kwake walipokosa kitu cha kula nyumbani.

Gutmann anatoa kumbukumbu ifuatayo iliyo wazi sana [ukumbusho] kumhusu Mangi Rindi na Petro Masamu katika “Das Recht der Dschagga” (labda kutoka mwaka wa 1884/85):

Wakati njaa ilipokuwa kubwa, watu walianza kufa kwa kukosa chakula. Kisha Mangi Rindi akaamuru kuchinjwa kwa ng’ombe katika vijiji kwa ajili ya kulisha wilaya, kila mmoja wa wakuu ng’ombe dume, kila maskini kipande cha mifugo midogo. Kuanzia wakati huo, alianza kila siku kuchinja ng’ombe waliokuwa wametekwa Uhonu. Kwa hiyo, wanaume waliacha mahitaji ya nyumbani kwa watoto na wakaenda kula kwa Mangi.

Nakumbuka Mangi Rindi tangu siku hizo: Nilikuwa nikichunga mbuzi siku moja nilipohisi njaa. Nikawakimbiza [mbuzi] nyumbani kwa haraka, lakini sikupata chochote cha kula na mama yangu hakuwepo kwani alikuwa ameenda kuomba ndizi zilizokaushwa. Niliondoka tena na mtoto wa jirani. Tulitembea katikati ya nyumba za Mangi. Ilikuwa mapema mchana. Tulimwona Mangi ameketi kati ya wake zake akila nyama. Nami nilikuwa mbele. Nilisimama kwa aibu kwenye kivuli cha nyumba mbili.

Kisha akaniona. Alikuwa karibu sana. Nilimsalimia, hakujibu na sikuweza kuthubutu kuketi chini. Kisha akauliza: „Wewe, mtoto wa nani?“ Nikamwambia. Kisha akauliza: „Wakati gani huu?“ „Njaa, bwana!“ Nikajibu. Kisha akakata kipande cha nyama kilichokuwa mbele yake na kunipa, akisema: „Chukua hii, mwanangu!“ Nikaichukua na kumshukuru. Aliniambia niketi chini nile na kunipa kisu chake. Watoto wengine, waliokuwa wakijificha, walipoona kinachonipata, nao walithubutu kuja karibu.

Ningependa kupeleka nyama nyumbani, lakini aliniamuru: „Keti chini ule na wenzako!“ Kwa hiyo tuliila na tukashiba wote.

Kisha Mangi akatuamuru: „Jipakeni mafuta!“ Tukajipaka mafuta.

Wakati huo huo, alikuwa akizungumza na mswahili mmoja aliyeitwa Mamdu.

Lakini sasa akamaliza mazungumzo naye na kugeukia kwetu kikamilifu. Na akatuambia: „Nini kinatawala sasa?“ „Njaa, Mangi!“ Na wenzako, wana hali gani?“ „Wanakufa, bwana!“ „Ndio, angalieni jinsi mawe yanavyorushwa kwao. Msije mkawa wezi.“ „Hapana, bwana!“ „Msije mkawa wezi!“ „Hapana, bwana!“ „Msije mkawa wezi!“ „Hapana, bwana!“ „Ukiiba, hata kama ni mkuu, hawezi kujinusuru dhidi ya kuvunjwa viungo kwa mawe!“ „Hapana, bwana!“ „Lakini usipoiba, hutakufa. Kama una njaa kweli kimbilia kwa Mangi na ukusanye mabaki kutoka kwenye uwanja wa uchinjaji wa wanaume. Usihofu kuja hapa.“ Na akamalizia kauli yake kwa maneno yale yale aliyokuwa akitumia kumaliza baraza la wanaume: „Pigeni hiwo!“ Na tukapiga kelele: „Hiwo!“ „Nendeni nyumbani, vijana wangu!“ „Ndio bwana!“ „Pigeni shangwe!“ Na tukapiga shangwe. Kwa hiyo tulirudi nyumbani, tukiwa na furaha kuu.

Imetafsiriwa kutoka Kiingereza na Elisia Mandara